Nova Scotia

Sydney, Nova Scotia, was briefly home to a chapter of the League for Democratic Rights, and there was a human rights committee with the Halifax and District Labour Council and the Cape Breton Labour Council, but the province had no active rights association until the Halifax Advisory Committee on Human Relations was created in 1962. During its fourteen-year history, it changed its name more often than any other rights association in Canada, reinventing itself as the Halifax Advisory Committee on Human Rights (1963), Nova Scotia Human Rights Association (1966), Nova Scotia Civil Liberties and Human Rights Association (1969), and the Nova Scotia Civil Liberties Association (1972). (The 1972 name change reflected the leadership’s desire to narrow the association’s activism to civil liberties issues after the province appointed a full-time director for the Human Rights Commission. Although Nova Scotia had passed human rights legislation in 1963, the association had played a key role in publicizing it and bringing cases before the commission, whose small staff operated out of the Ministry of Labour.)

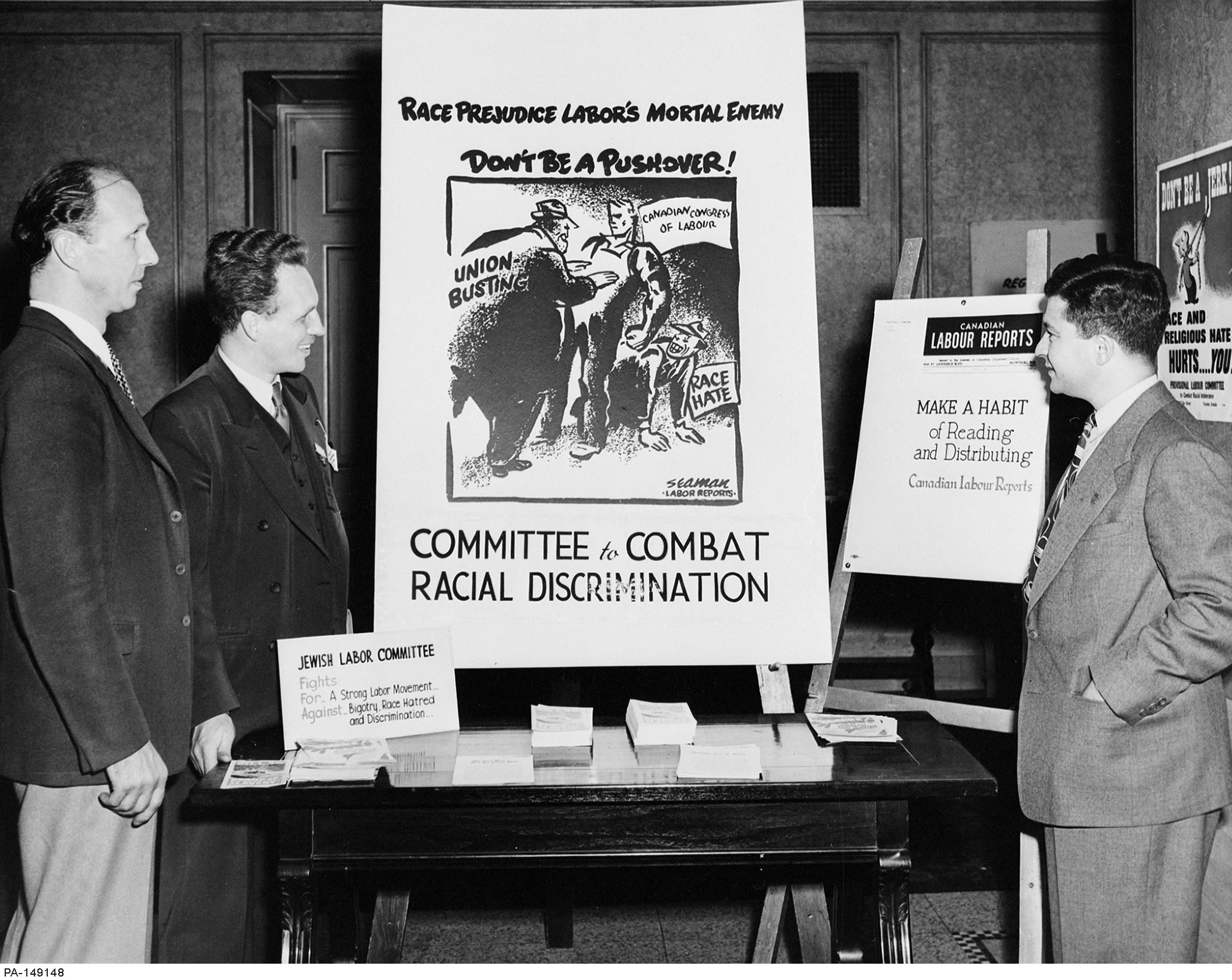

The original advisory committee arose due to efforts by the Jewish Labour Committee (JLC). Its director, Sid Blum, sent his most effective employee, Alan Borovoy, to Halifax in 1961 to work with the Nova Scotia Federation of Labour and other community groups in hopes of helping the population of Africville, an all-black suburb of Halifax. Africville was a flagrant example of racial segregation. Long a focus of concern for both local and national minority rights activists, it was a dilapidated neighbourhood of approximately eighty families (four hundred people), many of whom lived in hovels that lacked running water.

Working with Joe Gannon, a vice-president of the Canadian Labour Congress headquartered in Nova Scotia, Borovoy mobilized a group of activists to agitate for the rights of Africville residents, who eventually took the name of the Halifax Advisory Committee on Human Relations. Within a few years, Nova Scotia chief justice Gordon S. Cowan had become its president, and H.A.K. ‘Gus’ Wedderburn, president of the Nova Scotia Association for the Advancement of Coloured People, was its vice-chairman. By 1972, it had approximately 230 members. Wedderburn was its true driving force. A tireless black activist from Jamaica who had come to Canada in 1952, he was a high school principal, and he became the JLC representative in Halifax. For the next ten years, the Halifax group functioned in much the same capacity as the Ontario Labour Committee for Human Rights and received funding from the JLC. It established chapters in Pictou County, Truro, Cape Breton, and Yarmouth, but these did not last long.

The Halifax group was linked to the JLC solely through Wedderburn and did not depend on it for all of its funding. When the JLC expired in the 1980s, it continued to function with little hindrance, but by this time it too had begun to decline. After Wedderburn retired, it was run by lawyers and academics, most from Dalhousie University. In 1972, it became the Nova Scotia Civil Liberties Association, a name change that reflected its new mandate – that it would concentrate on civil liberties and leave discrimination cases to the Human Rights Commission, which it felt was better equipped to handle them. An article that covered the association’s February 1972 meeting recorded that, in the past, much of its energy had gone to fighting for the rights of minority groups, especially blacks and Aboriginals. But now that the human rights commission and the Black United Front were in operation, many association members believed that they could best serve the community by working to protect the civil liberties of all Canadians. The name change also reflected the organization’s decision to affiliate with the Canadian Civil Liberties Association. For the next three years, before it was discontinued in 1976, it focused on dealing with complaints against the police, reviewing legislation, and offering legal advice. Also in the early 1970s, it began to receive federal government grants: in 1971, the Canadian Mortgage and Housing Corporation awarded it $16,400 to organize tenants’ associations across the province, and the Secretary of State department allotted it $57,000 in 1973 to study doctor-patient relations. By 1976, it was led by Walter Thompson, a local lawyer, but when he could no longer organize its meetings, it ceased to be an active force in the province.

Halifax Advisory Committee on Human Relations (a.k.a.: Halifax Advisory Committee on Human Rights; Nova Scotia Human Rights Association; Nova Scotia Human Rights Federation; Nova Scotia Civil Liberties and Human Rights Association; Nova Scotia Civil Liberties Association) (chapters in Pictou County, Truro, Cape Breton, and Yarmouth)

Further Reading

Clément, Dominique. Canada’s Rights Revolution: Social Movements and Social Change, 1937-82. Vancouver: UBC Press, 2008.

Archives

Material on the rights associations of Nova Scotia is available at the Public Archives of Nova Scotia.

Site Resources

Site Resources-

- Any use of material or referencing content from HistoryOfRights.ca should be acknowledged by the User and cited as follows:

–

- Clément, Dominique. “page title or document title.” Canada’s Human Rights History. www.HistoryOfRights.ca (date accessed).

Encyclopaedia

Encyclopaedia

© 2024 COPYRIGHT CLÉMENT CONSULTING. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

DEPARTMENT OF SOCIOLOGY, UNIVERSITY OF ALBERTA

© 2024 COPYRIGHT CLÉMENT CONSULTING. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

DEPARTMENT OF SOCIOLOGY, UNIVERSITY OF ALBERTA