British Columbia

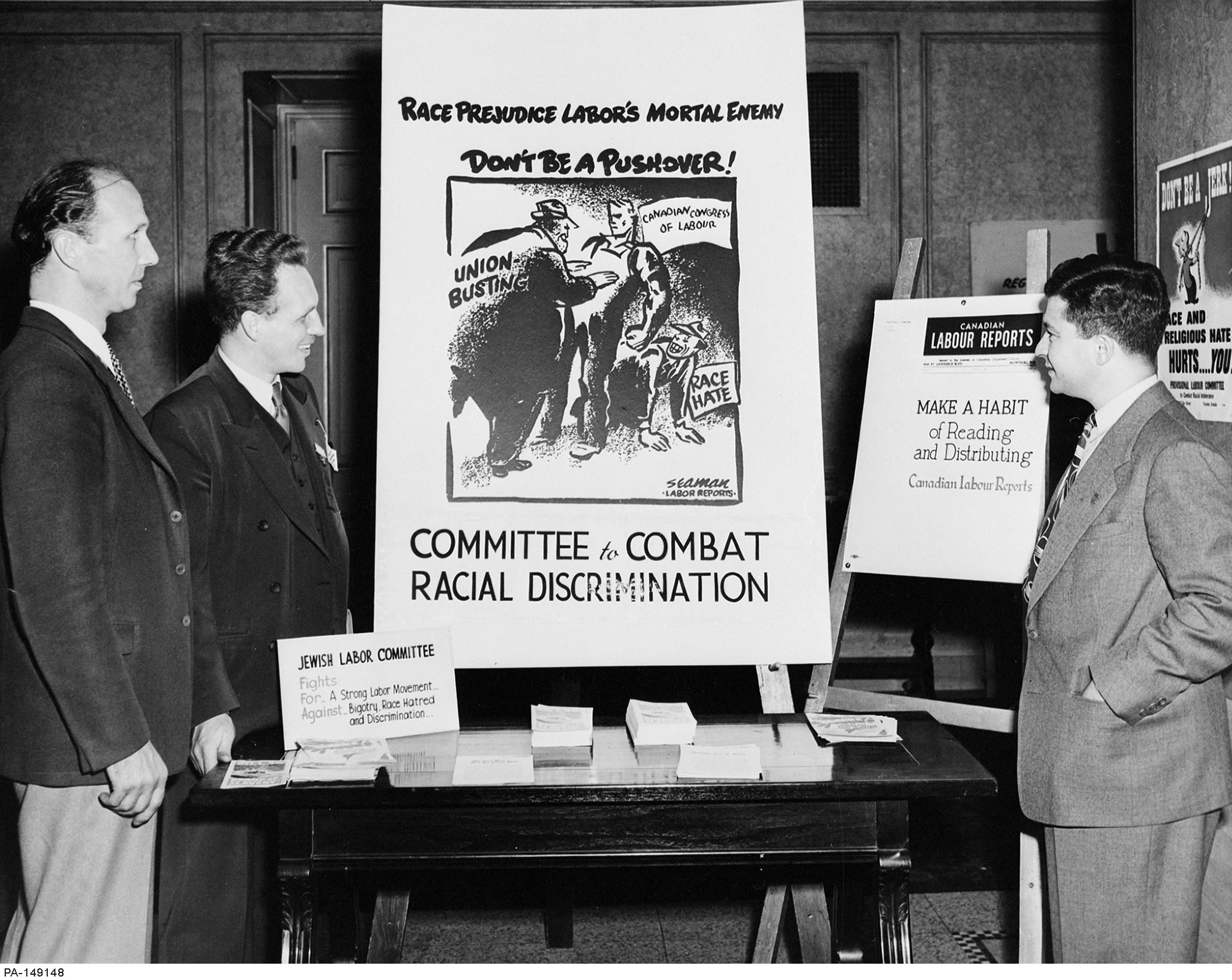

British Columbia’s first rights association, the Vancouver branch of the Canadian Civil Liberties Union (CCLU), was established during the 1930s under the leadership of Garnett G. Sedgewick, a well-known academic and social democrat. By the late 1950s, both the Association for Civil Liberties and the League for Democratic Rights had become inactive, and no rights associations remained in Canada. Nonetheless, anti-discrimination organizations existed in Vancouver throughout the 1950s, including a branch of the Jewish Labour Committee and the Vancouver Civic Unity Association, whose mandate was to improve relations between ethnic communities and to strive for the elimination of prejudice. The association was created in 1950 with leaders from local church, labour, and ethnic groups. Although it did not identify itself as a civil liberties or human rights organization, it did not speak on behalf of any specific constituency and was truly representative of the community. However, it was clearly issue-specific, with a mandate to focus on anti-discrimination campaigns, and thus it falls outside the rubric of a rights association. Indeed, in the wake of the Vancouver CCLU’s demise, neither it nor the local branch of the Jewish Labour Committee had inherited the mantle of a “rights association.” The first group to materialize from this vacuum was the BC Civil Liberties Association (BCCLA) in 1962.

Following the formation of the BCCLA, a host of other rights associations appeared throughout the province. In addition to the provincial and municipal human rights labour committees, a British Columbia Human Rights Council was created in the wake of International Year for Human Rights (1968). It was led by Joseph Katz, a well-known academic from the UBC Faculty of Education, who chaired the BC Human Rights Committee, the temporary body that organized the province’s activities for 1968. Katz was nationally acknowledged for his human rights work; his organization was one of the few to receive a large grant from the Secretary of State department in 1970, and in the following year, it was invited to Ottawa to join with a group of rights activists from across Canada in advising the Secretary of State department on its human rights program. Unlike the BCCLA, the council was a collection of associations, not individuals. One of its roles was to complement the provincial Human Rights Commission, which it did by conducting educational work and bringing human rights violations to the attention of the commission. Although it was involved in a variety of activities, its main focus was promoting non-discrimination and tolerance. As a result, it sometimes came into conflict with the BCCLA, whose civil libertarian stance prompted it to favour free speech even when such speech was hateful. Because of this incompatibility, the council hesitated to join the Canadian Federation of Civil Liberties and Human Rights Associations, fearing that civil liberties and human rights groups could never cooperate. In the end, however, it chose to join the federation and remained an enduring member until its own demise in the early 1980s. (As the council folded, the British Columbia Human Rights Coalition emerged to take its place. It too was an umbrella organization, not a membership of individuals. In addition, on issues such as pornography and hate propaganda, it favoured a broad human rights approach rather than the BCCLA’s civil liberties viewpoint.)

Whereas the BCCLA and the BC Human Rights Council were centred in Vancouver, many rights associations appeared throughout the province during the late 1970s. A 1969 attempt to launch a rights association in Victoria had proved unsuccessful, but another body was finally founded in 1979 and continues to operate today as a discussion group. At one point, groups existed in Powell River, Kamloops, Penticton, Quesnel, Prince George, Comox-Strathcona Courtenay, Kelowna, Williams Lake, and in the North-Central and South Okanagan. Some were organized by the BC Human Rights Council, but most were created by field workers with the BCCLA Community Information Project. Funded by a provincial grant in 1973 (and later by a Local Initiatives Program grant from the federal government), the Community Information Project sent field workers throughout the province to provide legal counselling services, promote good relations between the police and citizens, and encourage the formation of independent rights associations. Although the BCCLA was instrumental in their creation, it had no official links with them; none had representation on the BCCLA board of directors, and their sole financial relationship consisted of the salaries paid to the field workers through the BCCLA’s government grants. Unfortunately, the core weakness of each group was dependence on the field worker, and many collapsed when the field workers departed. Only the South Okanagan and Quesnel groups remain active today alongside the BC Civil Liberties Association.

British Columbia Human Rights Council

Kamloops Civil Liberties Society

Quesnel Civil Liberties and Human Rights Association

South Okanagan Civil Liberties Association

Victoria Civil Liberties Association

Williams Lake Civil Liberties Association

Further Reading

Clément, Dominique. Canada’s Rights Revolution: Social Movements and Social Change, 1937-82. Vancouver: UBC Press, 2008.

Clément, Dominique. “An Exercise in Futility? Regionalism, State Funding and Ideology as Obstacles to the Formation of a National Social Movement Organization in Canada.” BC Studies 146 (2005): 63-91.

Archives

The South Okanagan Civil Liberties Association Papers are available at the Royal BC Museum.

Site Resources

Site Resources-

- Any use of material or referencing content from HistoryOfRights.ca should be acknowledged by the User and cited as follows:

–

- Clément, Dominique. “page title or document title.” Canada’s Human Rights History. www.HistoryOfRights.ca (date accessed).

Encyclopaedia

Encyclopaedia

© 2024 COPYRIGHT CLÉMENT CONSULTING. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

DEPARTMENT OF SOCIOLOGY, UNIVERSITY OF ALBERTA

© 2024 COPYRIGHT CLÉMENT CONSULTING. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

DEPARTMENT OF SOCIOLOGY, UNIVERSITY OF ALBERTA