Duplessis Orphans

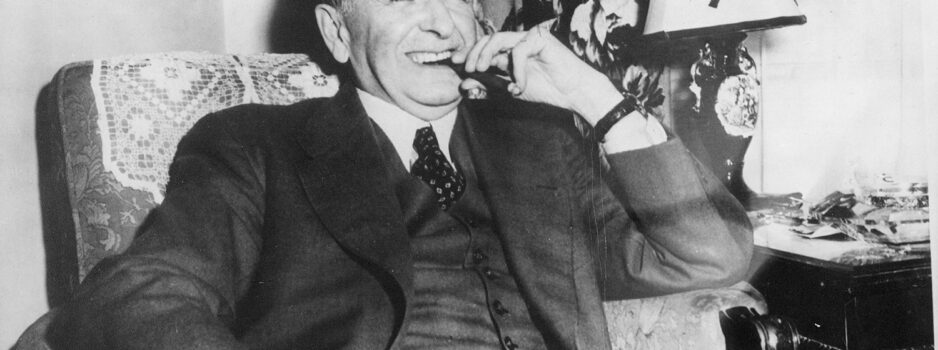

Maurice Duplessis | Copyright Dominique Clément / Clément Consulting

Even by the standards of mid-twentieth-century Canada, when discrimination was rampant and governments restricted fundamental freedoms, Maurice Duplessis stands out. His tenure as premier of Quebec (1936-39, 1944-59) is often referred to as le grande noirceur (the great darkness). By the 1950s, Duplessis had become associated with some of the worst instances of state abuse of civil liberties in Canadian history. One of these created the “Duplessis orphans.”

As premier, Duplessis (a childless bachelor) had a powerful ally in the Catholic Church, which was responsible for social services throughout the province, including orphanages. More than twenty thousand “illegitimate” children – of unmarried, often young, women – were born in Quebec between 1949 and 1956. The proportion of illegitimate children in the province was lower than in the rest of Canada, but the province had the highest rate of institutionalization and fewer adoptions. It was not uncommon for unwed mothers to be shamed into surrendering their children to the church; a powerful stigma was attached to unmarried motherhood, and abortion and the sale of contraception were criminal offences. Many children were also abandoned upon the death of a parent, and others were forcibly removed from their homes as a result of poverty, unemployment, sickness, or abuse. Children who grew up in Quebec orphanages faced a difficult life. Because of their status, they were exempted from compulsory schooling, a provision that endured for several years. The religious orders prioritized work over education; and the sons of unwed mothers could not legally inherit from their biological parents and could not become priests unless they had a special exemption. For many, this meant a life of deprivation, religious indoctrination, and feelings of guilt for their characterization as “children of sin.” And the church was poorly equipped to care for them. Orphanages had limited resources, and each nun was often responsible for watching at least ten children under the age of two. As the Quebec Ombudsman wrote in one of his reports on the investigation, “the majority of children spoke only in sounds until the ages of 4 to 6, and were incapable of telling time, eating with utensils, getting around, washing themselves, etc. In one trade school, up to 25% of the children between 9 and 16 were found to be bedwetters.”

The term “Duplessis orphans” refers to the cohort of children who suffered particularly traumatic abuse at the hands of the state and the Catholic Church: they were falsely diagnosed as mentally unfit and sent to psychiatric hospitals. The purpose of this was to maximize federal funding, which, at the time, was more generous for hospitals than for orphanages. The church was complicit in this scheme. In some instances, such as Mont-Providence, entire orphanages were reclassified as psychiatric institutions. When this occurred, the nuns’ relationship with their charges changed dramatically: they stopped educating the children, who were treated as “mentally deficient” patients. The Montreal Journal would later report that most of the children were improperly diagnosed: “Jean Gaudreau, a psychologist at the University of Montreal who visited one of the orphanages in 1961, said there is little doubt that children were unnecessarily institutionalized during that time. Tests conducted then showed, he said, that mental deficiencies were often caused by lack of stimulation, not mental illness.” [cited in NY Times, 5 March 1999] An estimated two to four thousand children were physically, mentally, and sexually abused. They were not treated when they became ill, and according to Paré et al. in “Les expériences vécues”, a survey of former orphans, they suffered the following abuses: “présence de règles injustes et de châtiments excessifs, abus physiques perpétrés par les personnes responsables, négligence émotive, exposition à de la violence perpétrée sur d’autres enfants par les personnes responsables, abus verbaux provenant des personnes responsables, négligence physique, abus sexuels perpétrés par les personnes responsables.” Many were forced to work as domestics, farmhands, or as help in church-run institutions such as hospitals – their pay was remitted to the orphanages. Several committed suicide, were killed, or struggled with mental illness. News reports claimed that some endured lobotomies, electroshock, straitjackets, and corporal punishment. When the province removed the orphans from psychiatric institutions in the 1960s (following the 1962 Bédard Commission report that recommended deinstitutionalization), they struggled to integrate into society. Many had difficulties with personal and romantic relationships, addictions, unemployment, and financial hardships. Most suffered from discrimination later in life. As Paré et al. write in “Les expériences vécues”, the “abus et la négligence subis par les [enfants de Duplessis] pendant l’enfance ont compromis leur ajustement psychosocial à long terme.”

The issue gained momentum in 1989, when the popular host of Radio-Québec’s Parler pour parler, Jeannette Bertrand, invited several Duplessis orphans to appear on her show. Pauline Gill’s 1991 exposé, L’histoire vraie d’Alice Quinton, drew further attention to their plight. In 1992, Bruno Roy, a Quebec-based writer and himself a Duplessis orphan, led an organization called the Duplessis Orphans’ Committee to secure redress from the Quebec government. Its initial attempts proved ineffective. A Quebec Superior Court rejected the committee’s petition for a class-action lawsuit, and it failed in its efforts to have criminal charges brought against the monks and nuns who were accused of abuse (many of the hospital files had been lost or destroyed). The committee also demanded apologies from the Quebec government, the Catholic Church, and the Quebec College of Physicians. Its campaign was bolstered in 1997 by a supportive report from the provincial ombudsman that recommended compensation. In Comments and Reflections by the Quebec Ombudsman, Daniel Jacoby offered the following remarks on the legacy of the Duplessis orphans and their campaign for redress:

“Each of the parties involved (government, the medical profession and religious communities) passes responsibility for the events on to the others or to the values of the period. Moreover, neither media coverage, nor petitions, criminal complaints, legal proceedings or appeals to the National Assembly or the different departments have until now allowed for reconciliating the different points of view or identifying specific responsibilities. Indeed, it is very difficult to go back in time and, after such a long time, specifically identify those responsible. Furthermore, the Superior Court, who had to rule on an authorization to file a class action, has itself been led to believe that legal recourse is not the appropriate avenue … Due to the limits of the judiciary system, the ‘Enfants de Duplessis’ now consider themselves the victims of a system of justice which they feel is hostile or inaccessible, since it does not allow them today to reveal or prove the injustices they allege … In fact, the government, medical profession or religious authorities have assumed responsibilities in such a way that, in practice, the ‘Enfants de Duplessis’ continue to suffer the wrongdoings for which they have never been compensated … The social context at the time cannot justify that persons, following medical certificates issued for financial rather than medical reasons (grants obtained), have been confined in asylums, neither can it justify certain abuses. Today’s society has the obligation to officially acknowledge the wrongdoings caused to its citizens.”

In 1999, the government finally apologized and offered $3 million in compensation, which was rejected. Jacoby described the offer as unfair and humiliating. The Catholic Church refused to apologize or provide compensation. Following extensive publicity and public pressure, the Quebec government extended another apology in 2001 as well as individual compensation of $10,000 plus $1,000 for each year spent in an asylum (1,500 people qualified for compensation). The Duplessis Orphans’ Committee accepted the offer, and the government provided an additional $26 million compensation in 2006.

The scandal of the Duplessis orphans raises several human rights issues. From a human rights perspective, children occupy a unique place. As Micheline Dumont suggests in “Des religieuses”, “‘les enfants de Duplessis’, est passé du statut le plus ingrat de la société, parias sans existence légale qu’on dissimulait soigneusement derrière les murs d’institutions gigantesques, à celui de personnes lésées dans leurs droits fondamentaux. Dans notre nouvelle société de droits, ce statut confère une notoriété certaine.” In the 1970s, several provinces introduced legislation to recognize children’s rights. Quebec’s Youth Protection Act of 1977, for instance, guaranteed that youths would be consulted about changing their foster parents and could speak with a lawyer before judicial proceedings; the Ontario Child Welfare Act of 1978 protected the privacy of adopted children. And yet, with the exception of prisoners, only children are denied the fundamental rights that other human beings enjoy in Canada (such as the franchise, freedom of movement, and the ability to enter into a contract). In this way, they are uniquely vulnerable to human rights abuses, as the Duplessis orphans exemplify.

Chronology

1964: Jean-Guy Labrosse publishes Ma Chienne de vie, about his experience as a Duplessis orphan

1965: Noël Flavien founds the Association des Orphelins du Québec d’avant 1964

1989: Jeannette Bertrand’s Radio-Québec episode on the Duplessis orphans

1991: Pauline Gill publishes L’histoire vraie d’Alice Quinton

1992: Duplessis Orphans’ Committee (Comité des orphelins de Duplessis) founded

1994: Bruno Roy publishes Mémoire d’asile

1995: Attorney general announces that there is insufficient evidence to proceed with criminal complaints against church members

1997: Quebec ombudsman report The “Children of Duplessis”

1999: Quebec government apologizes and offers $3 million in compensation

1999: Catholic Church rejects demand for an apology and compensation

2001: Quebec government offers an apology and individual compensation of $10,000 plus $1,000 for each year spent in an asylum. The Duplessis Orphans’ Committee accepts the offer

2006: Quebec government provides an additional $26 million in compensation, with the caveat that individuals must agree not to pursue legal action against either itself or the church

2010: Bruno Roy dies on 5 January

Further Reading

Baugé-Prévost, Jacques. Plaidoyer d’un ex-orphelin réprouvé de Duplessis. Library and Archives Canada Amicus no. 22143105.

Le programme national de réconciliation avec les orphelins de Duplessis ayant fréquenté certaines institutions. Bibliothèque et archives nationales du Québec.

Programme national de réconciliation avec les orphelins et orphelines de Duplessis: demande d’aide financière: guide du demandeur. Bibliothèque et archives nationales du Québec.

Sigal, John, et al. Health and Psychosocial Adaptation of les Enfants de Duplessis as Middle-Aged Adults: Final Report. Library and Archives Canada Amicus no. 27771264.

Vienneau, Rod. Les enfants de la grande noirceur: les orphelins de Duplessis: revelations chocs par la Commission pour les victims de crimes contre l’humanite dans le dossier des orphelins de Duplessis. Library and Archives Canada Amicus no. 33978709.

Duplessis Orphans, CBC Digital Archives.

Les Orphelins de Duplessis, Ciné Télé Action International television mini-series 1999, DVD version 2007.

Orphelins de Duplessis, Radio-Canada Archives.

Québec: Duplessis and After, National Film Board 1972.

Dufour, Rose. Naître rien: Des orphelins de Duplessis, de la crèche à l’asile. Sainte-Foy: Éditions MultiMondes, 2002.

Dumont, Micheline. “Des religieuses, des murs et des enfants.” L’Action nationale 84, 4 (1994): 483-508.

Gill, Pauline. L’histoire vraie d’Alice Quinton, orpheline enfermée dans un asile à l’âge de 7 ans. Montreal: Editions Libre Expression, 1991.

Malouin, Marie-Paule. L’univers des enfants en difficulté au Québec entre 1940 et 1960. Montreal: Bellarmin, 1996.

Nootens, Thierry. “Mémoire, espace public et désordres du discours historique: l’affaire des orphelins de Duplessis 1991-1999.” Bulletin d’histoire politique 7, 3 (1999): 97-107.

Paré, Nikolas, John J. Sigal, J. Christopher Perry, Sophie Boucher, and Marie Claude Ouimet. “Les expériences vécues par les enfants de Duplessis institutionnalisés: Les conséquences après plus de 50 ans.” Santé mentale au Québec 35, 1 (2010): 85-109.

Quebec Ombudsman. The “Children of Duplessis”: A Time for Solidarity: Discussion and Consultation Paper for Decision-Making Purposes. 1997.

Quebec Ombudsman. Comments and Reflections by the Quebec Ombudsman. 1997.

Roy, Bruno. Mémoire d’asile. Montreal: Boréal, 1994.

Turenne, Martine. “La veritable histoire des Orphelins de Duplessis.” L’actualité 22, 11 (July 1997): 51-58.

Site Resources

Site Resources-

- Any use of material or referencing content from HistoryOfRights.ca should be acknowledged by the User and cited as follows:

–

- Clément, Dominique. “page title or document title.” Canada’s Human Rights History. www.HistoryOfRights.ca (date accessed).

Encyclopaedia

Encyclopaedia

© 2024 COPYRIGHT CLÉMENT CONSULTING. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

DEPARTMENT OF SOCIOLOGY, UNIVERSITY OF ALBERTA

© 2024 COPYRIGHT CLÉMENT CONSULTING. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

DEPARTMENT OF SOCIOLOGY, UNIVERSITY OF ALBERTA