A Hypothetical Case

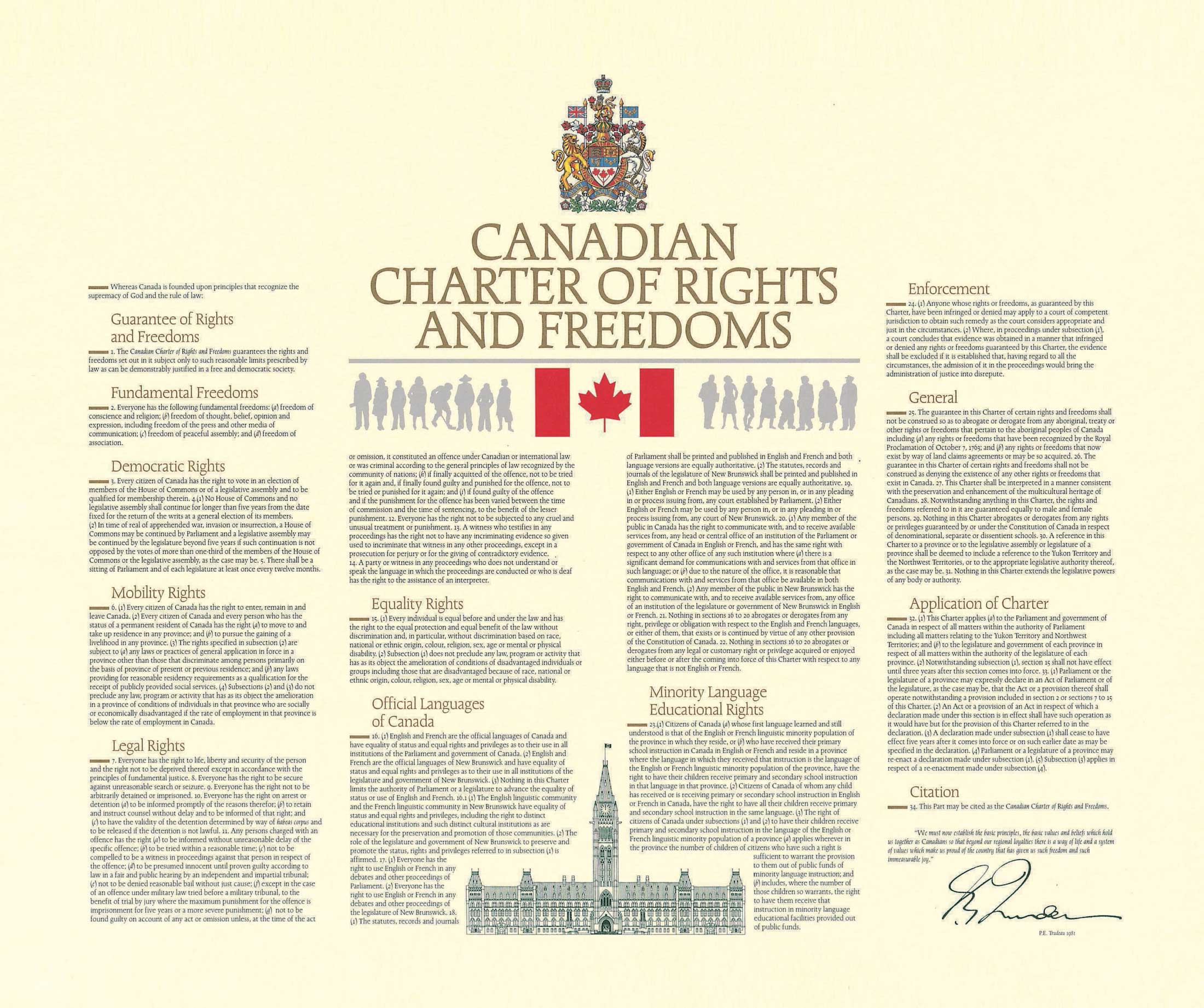

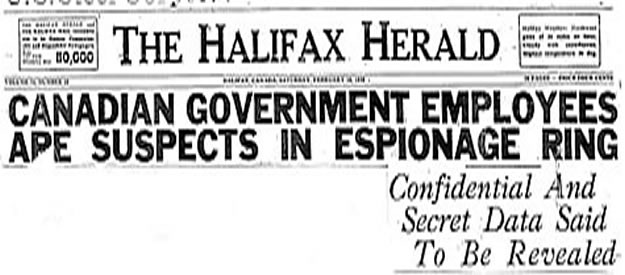

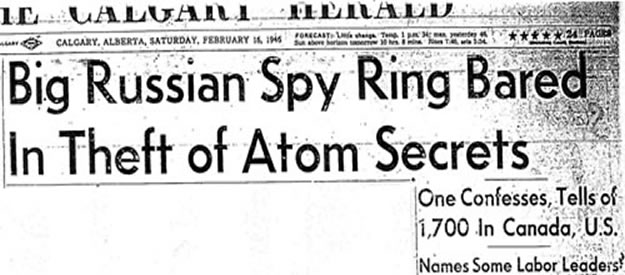

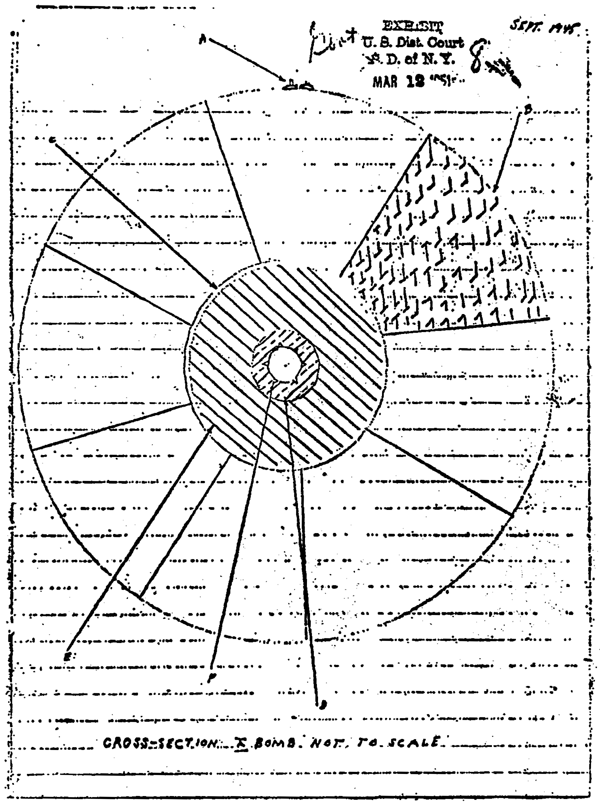

The following article appeared in the 2 July 1947 issue of the Fortnightly Law Journal (author unknown, vol. 17: 43). It is reproduced verbatim below, including the Editorial Note with which it concludes. It discusses a hypothetical case to emphasize the potentially dangerous legal precedent set by the espionage commission, and though it deals with murder, it nonetheless demonstrates how, in its efforts to coerce a confession, the state could use 1946 legislation to circumvent an individual’s basic liberties.

“Dinn v. The King, July 4, 1949. (Evidence – Admissibility of evidence before a Royal Commission on the charge of murder)

Roy Dinn, husband of the accused, had disappeared on November 23rd, 1947, and his body had been found six days later in an empty cage at Riverdale Zoo at Toronto, Ontario. The Accused had been immediately arrested on a charge of vagrancy, and at the request of the Attorney-General for Ontario, a Royal Commission had been issued under an unpublished order-in-council by the Dominion Government and under the direction of Voltai and Addison, JJ., of the Supreme Court of Canada, to inquire secretly into the death of Roy Dinn, pursuant to the Inquiries Act, R.S.C. 1927, Chapter 99. The accused had been handed over to the custody of the R.C.M.P. and had been held incommunicado for six months without any further charge having been laid. She had been brought before the Royal Commissioners three times in secret session, and had refused to be sworn and had demanded counsel. The Commissioners had informed her that as there was no charge against her she was not entitled to counsel under ss. 12 and 13 of the Inquiries Act, unless the Commissioners in their discretion allowed her request and that, in their discretion they refused it. On June 2nd, 1948, accused again had been brought before the Commission at a secret hearing and informed that she must be sworn and answer all questions. She was not advised that if she answered questions without objection her answers could be later used in evidence against her, nor was she advised that if she objected to answer any question on the ground that her answer might incriminate her.She had been kept in solitary confinement in a brilliantly lighted cell for three days. In response to questions by the Commission counsel accused had admitted, without objection, responsibility for the murder of her husband. A charge of murder was then laid against her.

At the trial the testimony of the accused so obtained had been admitted on the authority of, R v. Mazerall [1946] O.R. 762, R v. Lunan, [1947] O.W.N. 248, and R v. Smith, [1947] O.W.N. 449 (‘spy trials’).

Although there was no other evidence implicating the accused, she had been convicted. An appeal to the Court of Appeal had been dismissed.

Rousseau, C.J.C., delivering the judgment of the Court, held that R v. Dick, [1947] O.W.N. 111, was not applicable. The treatment of the accused leading up to her confession was irrelevant. The Commissioners had acted perfectly properly in every respect, they were not obliged to allow counsel to the accused, since, until she confessed, there was no possibility of bringing a charge of murder against her; the Commissioners were not obliged to advise the accused concerning the effect of s. 5 of the Evidence Act, R.S.C. 1927, c. 69. Methods of obtaining evidence on charges under the Official Secrets Act, 1939 (can.), Chapter 49, were available, a fortiori, in investigating a charge of murder. The evidence had been properly admitted and the conviction must be affirmed.

The appeal was accordingly dismissed.

EDITORIAL NOTE. This case marks a milestone in the investigation of crime in Canada. It is astonishing that no Attorney-General had previously thought of the means used to obtain evidence in this murder. It may be assumed that the precedent will be generally followed, and we recommend that seventy-three additional Judges be appointed to the Supreme Court of Canada, in order that a sufficient number of Commissioners be constantly detailed and what has been hitherto the ordinary business of the Court may also be carried on. Independence Day of the great Republic to the south was obviously the appropriate day on which to deliver this judgment.”

Further Reading

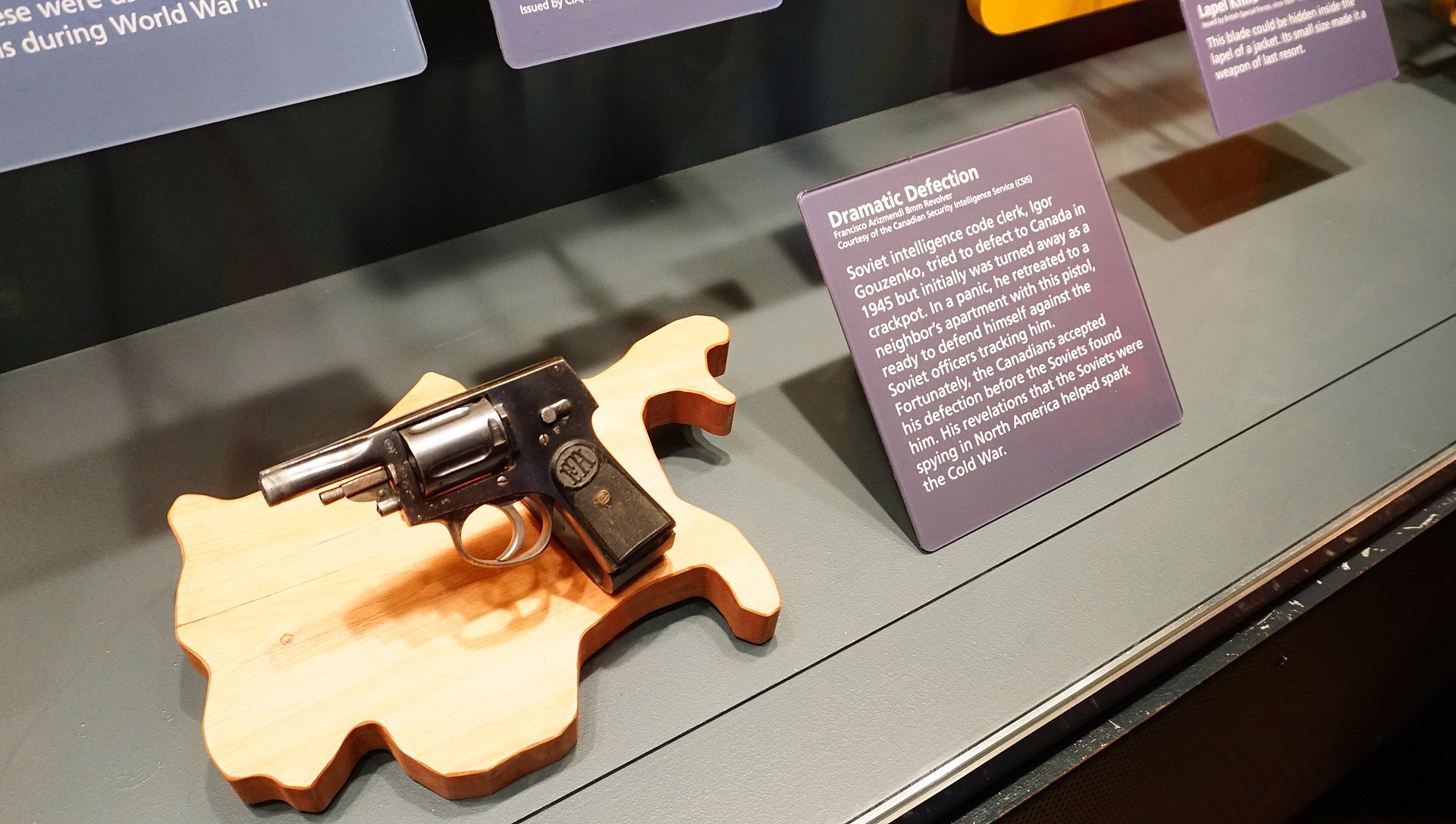

There is a great deal more to learn about the Gouzenko Affair. To continue, please follow one of the links on the right including Chronology, Sentences, Key Figures, Archives or Further Reading. For some initial readings, see:

- Clément, Dominique. “The Royal Commission on Espionage and the Spy Trials of 1946-9: A Case Study in Parliamentary Supremacy.” Journal of the Canadian Historical Association 11, 1 (2000): 151-72.

- Clément, Dominique. “Spies, Lies and a Commission, 1946-8: A Case Study in the Mobilization of the Canadian Civil Liberties Movement.” Left History 7, 2 (2001): 53-79.

- Knight, Amy. How the Cold War Began: The Gouzenko Affair and the Hunt for Soviet Spies. Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 2005.

- Lambertson, Ross. Repression and Resistance: Canadian Human Rights Activists, 1930-1960. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2005.