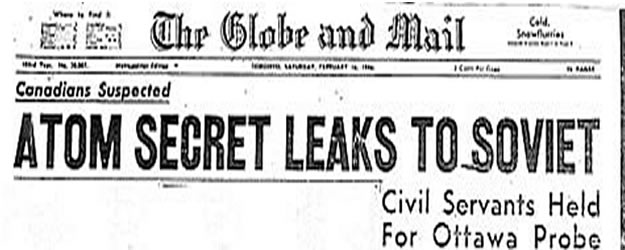

The espionage commission was mandated to investigate violations of the Official Secrets Act. According to section 3 of the statute, anyone who acted “for any purpose prejudicial to the safety or interests of the State” in obtaining and relaying information that was “useful to a foreign power” was “guilty of an offence under this Act.” Although British common law presumed that an individual was innocent unless proven guilty, the Official Secrets Act contained an unusual provision: the onus of proof was reversed. Accused individuals were presumed to be guilty, and the burden was on them to prove their innocence. Thus, those who were accused of communicating top-secret information and could not prove their innocence were guilty.

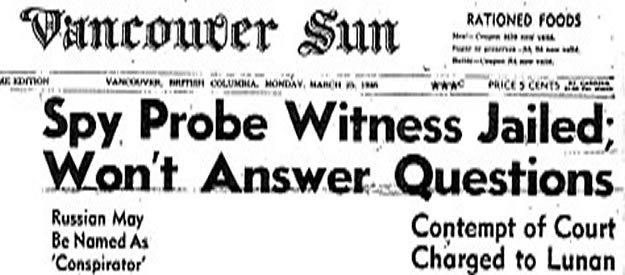

The commissioners were asked to determine whether anyone had violated the Official Secrets Act. However, the commission’s powers were defined by the Inquiries Act (all federal royal commissions, then and now, are created under the authority of this act). Under its provisions, royal commissioners had the power of “summoning before them any witnesses, and of requiring them to give evidence on oath.” They could also “compel them to give evidence as is vested in any court of record in civil cases.” Anyone who refused to testify could be charged with contempt and sent to jail. A 1912 amendment to the statute further stipulated that “commissioners may allow any person whose conduct is being investigated under this Act … to be represented by counsel.”

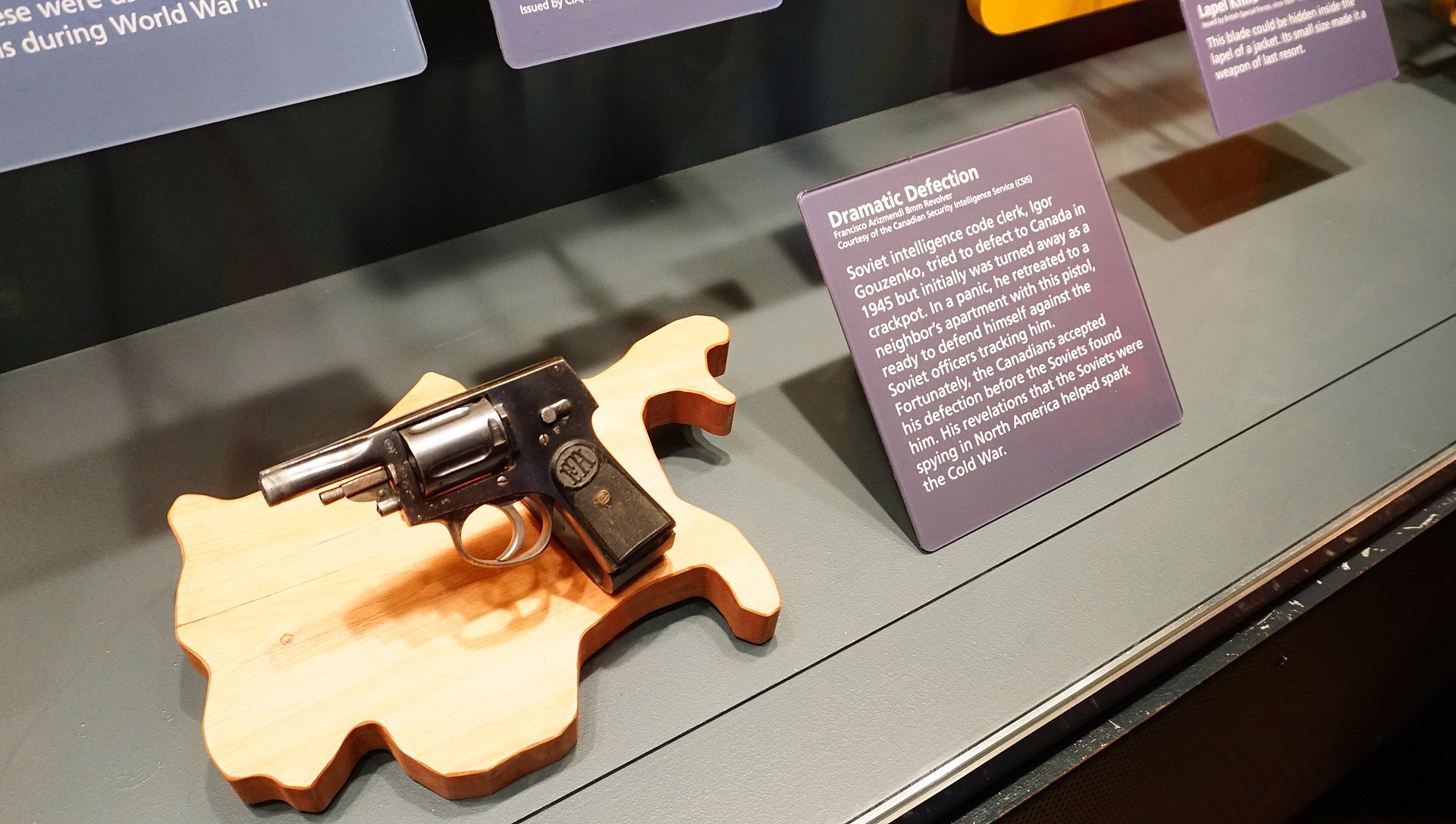

The unique situation in which a royal commission, with the powers granted under the Inquiries Act, investigated a violation of the Official Secrets Act, with its reverse onus of proof, created a rare and disturbing opportunity for the federal government to circumvent traditional liberties. Of course, the royal commission was not a court and could not send people to jail. Instead, as mentioned above, the government employed it to gather information that would later be used to prosecute suspects for violating the Official Secrets Act. Although Ottawa’s case relied on circumstantial evidence, the reverse onus of proof in the Official Secrets Act allowed it to base its prosecution primarily on Gouzenko’s testimony, the commission transcripts, and the stolen documents from the Soviet embassy. (In addition, most suspects were charged only with conspiracy to violate the Official Secrets Act, which required a lesser burden of proof than was necessary for a direct violation of the statute.)

Critics were especially concerned with the government’s decision to use the powers of the War Measures Act months after it had been rendered inoperative. The Second World War had ended in August 1945, and the government claimed in January 1946 that it was no longer using the War Measures Act. (When the act was revoked in December 1945, some special wartime powers continued under the National Emergency Transition Powers Act to enable the government to deal with post-war reconstruction.) Only two Orders-in-Council passed under wartime powers remained in play after December 1945: PC6444 and the order to deport Japanese Canadians. However, PC6444 and the Gouzenko defection still remained top secret. (In January 1946, when John Diefenbaker asked St. Laurent in Parliament whether any Orders-in-Council enabled under wartime powers were still in operation, St. Laurent replied negatively. Later, after the defection became public, he claimed to have forgotten about PC6444.)

It is crucial to appreciate the chronology of these events. The War Measures Act was set to expire on 31 December 1945. In October 1945, the prime minister and two members of his cabinet signed Order-in-Council PC6444, which authorized the minister of justice “to order the detention of such persons in such places and under such conditions as the Acting Prime Minister or Minister of Justice may from time to time determine.” Several months later, on 5 February 1946, the prime minister signed Order-in-Council PC411, which established the espionage commission. Technically, the commission was not linked to PC6444. However, royal commissions cannot arrest and detain people. Habeas corpus, a traditional legal right, allowed any individual held by the state to appear before a judge to determine the legitimacy of his or her detention (e.g., an indictment against the individual or the denial of bail by a judge). PC6444, passed under the authority of the War Measures Act when it was still operational, allowed the government to hold suspects indefinitely without evidence. Several months after the end of the war, Ottawa was using wartime powers to detain suspected criminals.

In 1946, a writer for Maclean’s magazine suggested that “in place of an honourable contrast (to communism), the commission provided a superficial but still ugly resemblance to the procedures normal in a totalitarian regime.” Many concerned lawyers pointed out that, under the provisions of the federal Canada Evidence Act, judges could grant immunity to witnesses against self-incrimination. If the commission’s true intent were to gather information, not to circumvent the legal system, why did the justices not protect the witnesses against incriminating themselves?

Commissioners Roy Lindsay Kellock and Robert Taschereau responded to public criticisms of their tactics in their final report. They pointed out that the Canada Evidence Act was designed to ensure that fear and coercion did not motivate confessions (to avoid false confessions and to discourage the police from using abusive measures). Did holding people for weeks, subjecting them to numerous interrogations, and refusing to let them have visitors qualify as “fear and coercion”? The commissioners did not think so. Their final report distinguished between their mandate and a normal criminal investigation. The Canada Evidence Act was designed to protect witnesses from having their testimony used against them in court – it was applicable only to individuals who were accused of a crime. The commissioners claimed that because they never charged anyone with a crime and were simply conducting an inquiry, they were not required to inform people of their rights under the Canada Evidence Act. As they explained in the final report, “In not warning the witnesses, we have then followed the only legal course open to us.”