Incarcerated in the RCMP’s Rockcliffe Barracks in Ottawa, the suspected spies were not charged and had no access to visitors or a lawyer. Some were detained for as long as five weeks. Initially, RCMP officers interrogated each suspect individually and pressured him or her to confess. After several of these “sessions,” the suspects were brought before the espionage commission and advised that testifying was in their best interest. They were also informed that the law required them to speak and that they were simply appearing before an inquiry. A royal commission, as they were repeatedly told, was not a court of law, and they themselves were “witnesses” who were not being charged with a crime. If they declined to speak, they risked six months in prison for contempt of the commission. Those who refused to testify were returned to their cells until they became more amenable. Detained for weeks without legal counsel, several suspects eventually provided the commission with information, unaware that its primary goal was to solicit material that could later be used against them in court.

At the time, the British high commissioner to Canada surmised that “it is not only a commission appointed to report to Parliament on a general question, but also it inevitably constituted itself a judicial tribunal, in effect, to try certain persons of suspected illegal activities, without any actual charge being laid against them.” (Hyde, The Atom Bomb Spies). He was proved right many years later, when the federal government released several top-secret documents relating to the commission, including E.K. Williams’ infamous memorandum (see primary documents), which recommended its creation. As the documents reveal, the commission coerced confessions from several people whose testimony was later used against them in court, thus circumventing the legal safeguards against self-incrimination.

During his incarceration, detainee David Shugar wrote several letters to members of Parliament, describing the conditions in which he was held. His cell was a small room, about nine by eight feet, and its 100-watt light bulbs shone twenty-four hours a day (the suspects were held under suicide watch). An RCMP officer was posted beside his cell at all times. Shugar was denied access to a lawyer and was threatened with prison if he refused to testify. After a failed hunger strike, he wrote a letter to Justice Minister Louis St. Laurent on 9 March 1946 in which he lamented that “if I am to judge by the treatment accorded to me yesterday afternoon before your Royal Commission, I can only come to the conclusion that, as a Canadian citizen, I have been completely stripped of all my rights before the law.” Because Shugar and his fellow suspects were held incommunicado, they had no idea that the government had passed an Order-in-Council (PC6444) to legalize their detention under the War Measures Act.

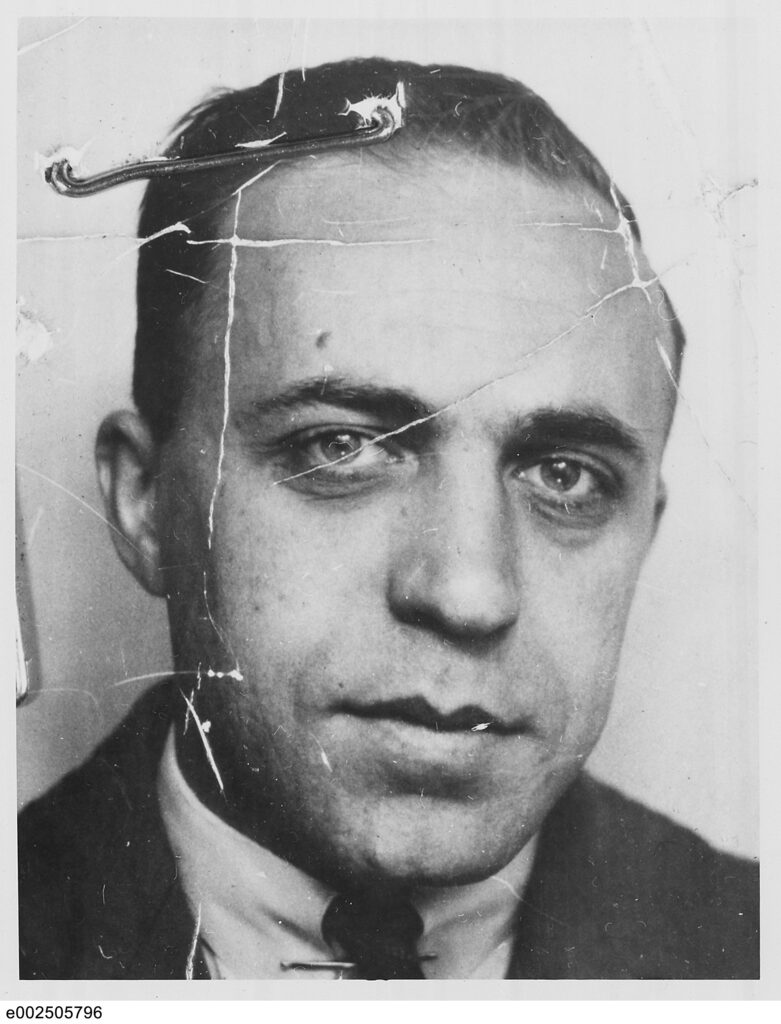

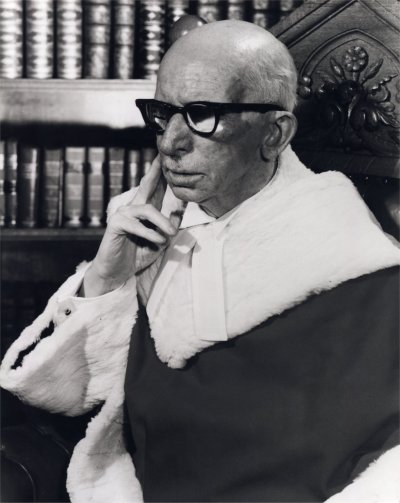

One can only imagine the immense pressure that the detainees experienced after weeks of solitary confinement. Only those who submitted to the commission and answered its questions were granted an early release. Given the stress of the situation and the prisoners’ unfamiliarity with the legal system, it is not surprising that several soon confessed. The fact that the commission was chaired by two Supreme Court judges, Roy Lindsay Kellock and Robert Taschereau, undoubtedly exacerbated their confusion about their rights and obligations. Stubborn prisoners were allowed access to legal counsel only after several weeks. It is possible that the commissioners permitted some people to see a lawyer only because of the intense criticism in the press, particularly after the publication of the commission’s first interim report. Although the press generally approved Ottawa’s actions, and certainly had no sympathy for accused communist spies, several newspaper editors were concerned that the government had been holding people incommunicado and without charges since 15 February 1946. The unusual (and abusive) measures that characterized the arrest and detention of thirteen accused spies were later widely criticized by members of the press, the legal profession, civil liberties organizations, and politicians in Canada and abroad.