Security at the Montreal Olympics

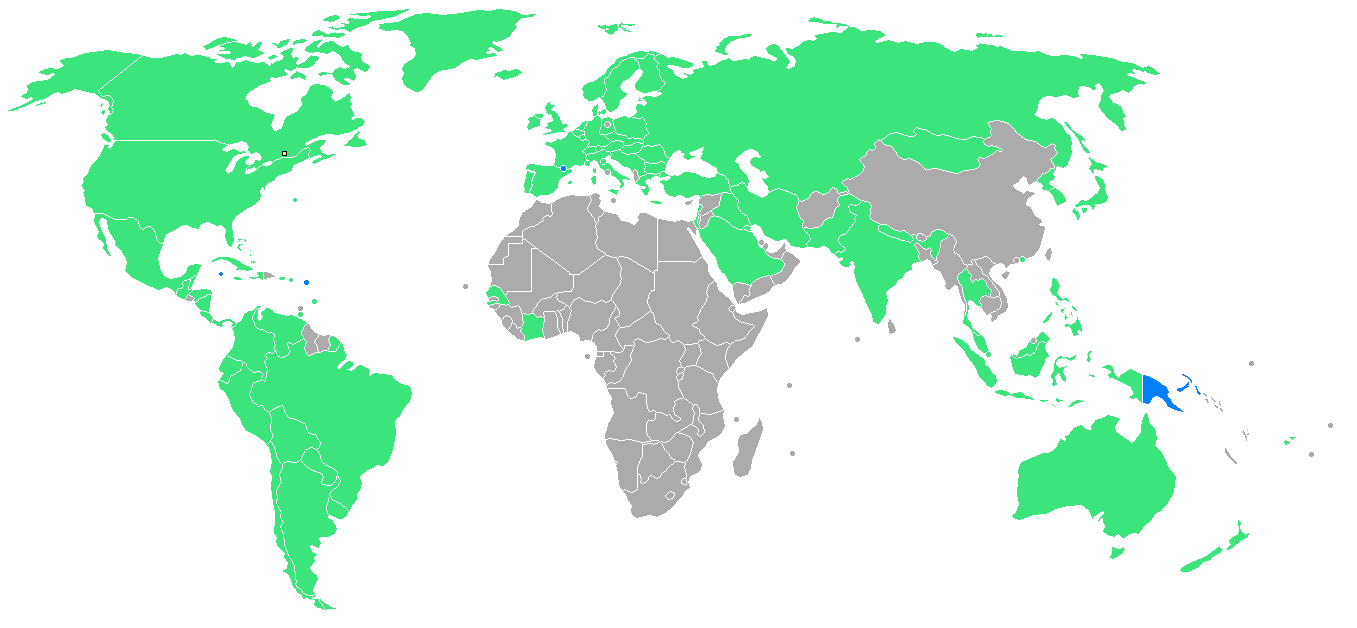

Security for the games was an immense operation. The RCMP conducted 94,147 security checks on athletes, dignitaries, employees, media and concessionaires (185 were flagged as potential security threats). It was responsible, with help from the Canadian Forces, for providing security for foreign dignitaries, airports and border patrols as well as providing security for the Royal Family and 121 VIPs. Cognizant of what happened in Munich, the RCMP established a heavy presence in the Village and accompanied athletes as they travelled within Canada.

The plan was to have an obvious physical security presence that was, at the same time, not intimidating. A security force of 17,224 was assigned to the Olympics: 8,940 Canadian Forces; 1,606 Montreal Urban Community Police; 1,376 RCMP; and 1,140 Sûreté du Québec. Security personnel also included officers from the Metropolitan Toronto Police, Ontario Province Police, National Harbours Board Police, Manpower and Immigration, the Montreal Fire Department and 2,910 private security guards hired by the Olympic committee. Security was provided for 13 competition sites and 27 training sites, as well as the Village. The Sûreté du Québec alone drew officers from 47 detachments across the province scattered over six districts, and drove 1,462,159 miles in 26 vehicles (and 112 hours in helicopters) over the 46 day operation. More than 32,000 security checks and guarding operations were conducted. Most of the major federal ministries, including National Defence, Immigration, Revenue, and Transport were implicated in the operation. The entire national police force was mobilized to deal with the Olympics. Leave was suspended for many RCMP officers outside Ontario and Quebec to avoid creating dangerous gaps in security. In order to secure sufficient bilingual officers as well as those with specialized training (eg. hostage negotiations or snipers), the force was required to transport officers from all over the country to Montreal.

The overall operation was impressive. Altogether, more than 17,000 police and military personnel were mobilized to protect fewer than 6000 athletes. A major command and control centre was established in the RCMP’s renovated “C” division headquarters in Montreal to coordinate among the various agencies, and a smaller headquarters was also established in Kingston. The Kingston and Montreal centres constituted the heart of the Olympic security communications network, albeit there were also special command centres in “A” division and the RCMP headquarters to provide communication links among senior managers and the venues. Rather than spreading the Village across the city (as was the case in Munich), the Montreal Olympic Village was a towering 19 story pyramidal structure with limited access and a ten-foot high wire fence. Athletes were driven to competition sites on buses with armed soldiers or police officers, while soldiers with automatic weapons patrolled the Village.

The Montreal Olympics was a testament to the diverse and widespread nature of security planning that would become the norm for future Olympics hosts. The National Security Plan included air security (restricted air space); controlling ports of entry at land, air and sea; harbour security; postal security (a detection centre to screen all mail destined for Olympic sites); and public relations and security briefings. Surveillance of side roads and rural areas was increased to prevent unauthorized entry into the country. Several “vital points” were identified, such as nuclear and hydro power plants, and given extra security from the Canadian Forces. Military personnel who were assigned the assist the police were deputized as law enforcement officers, which authorized soldiers in the absence of a policeman to arrest anyone breaking a law. National Harbours Board Patrol officers were temporarily appointed Immigration Officers at points of entry. The federal government passed special immigration legislation allowing the minister of immigration to deport anyone who might engage in violence during the Olympics. It was an unusual statute: only one sentence, which gave the minister unfettered power to deport non-citizens with no right to appeal. Cabinet also revised, on the eve of the Olympics, its policy from 1967 for excluding immigrants who were considered security threats. The updated criteria made specific reference to terrorists and certain criminal activities while removing the long-standing prohibition on individuals who belonged to communist and socialist parties abroad. Meanwhile, local law enforcement was dramatically enhanced, including an expanded drug squad, a “scalper” squad targeting illegal ticket sellers, and a squad of 24 officers to police pickpockets. As a result, the crime rate in Montreal dropped by more than 20 per cent during the games (there was also a decline in Criminal Code violations on local waterways as a result of increased harbour patrols). Even compared to much larger countries, this was an imposing security operation.