The Road to Montreal

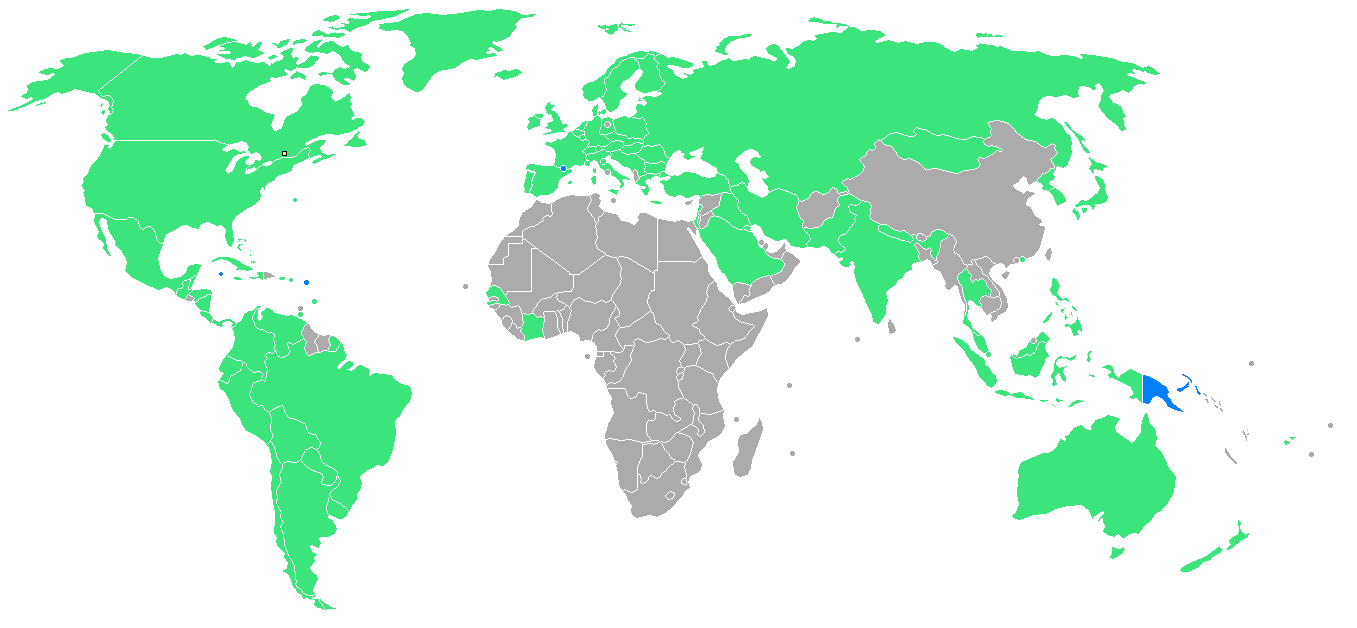

The Montreal Olympics remains to this day the largest sporting event in Canadian history. It was also the most controversial. The games were awarded to the city in May 1970. A few months later, Canada became one of the first western nations to recognize the People’s Republic of China. This created an untenable situation. Taiwan had been a member of the International Olympic Committee for many years, and insisted on being called the Republic of China and flying the Nationalists’ Chinese flag. China, on the other hand, adamantly refused to participate alongside Taiwan. There were intensive negotiations with Taiwan and China, but the federal government was resolute that Taiwan could not participate in the games while claiming to represent China. When the United States threatened to boycott if Taiwan was banned, the International Olympic Committee seriously considered cancelling the games. In the end, both Taiwan and China withdrew mere days before the opening ceremonies. Meanwhile, twenty-nine African countries as well as Iraq insisted on banning New Zealand from competing in Montreal. The African nations were advocating a worldwide sports boycott against South Africa to protest apartheid, which New Zealand ignored. When Canada and the International Olympic Committee refused to negotiate, most of the African states withdrew.

To make matters worse, soaring costs threatened to cancel the games. Mayor Jean Drapeau had so badly underestimated the cost that the National Assembly hauled him before an inquiry to explain the situation. The province established an Olympic Installation Board, which took ownership and responsibility for constructing the venues. It also introduced emergency legislation in 1973 to force a settlement on striking ironworkers and to send them back to work on Olympic venues. Soon after, the media reported that the police had raided the Olympic Village construction site as part of an investigation into allegations of corruption and ties to organized crime.

It was not long before people began to realize that the games were a financial disaster. The Summer Olympics in Tokyo (1964, $9 million), Mexico City (1968, $12 million) and Munich (1972, $495 million) were dwarfed by the more than $1.5 billion spent in Montreal. With the exception of Moscow (1980, $1.3 billion), subsequent games in Los Angeles (1984, $408 million) and Seoul (1988, $531 million) were nowhere near as costly (although more recent Olympics have vastly overshadowed Montreal even after accounting for inflation, including the estimated $50 billion spent on the Sochi Olympics in Russia in 2014). Unlike other host cities at the time with existing sports infrastructure, Montreal had to build most of its venues. Social services suffered and several projects had to be put on hold. A water treatment plant, for instance, was delayed until 1981. For many years after the Olympics, Montreal was the only major city in North America that was still dumping waste into adjacent waterways.

The Montreal Olympics set precedents in many other ways. The participation of Indigenous peoples in Olympic ceremonies, which occurred in large numbers for the first time in Montreal, has since become the norm for Olympics in Canada, Australia and the United States. One of the major events, the equestrian competition, was held on private lands for the first time in Olympic history. It was, according to author Paul Howell, one of the first major sporting events that combined formal project management with new computer technology. Unlike past Olympics, which have traditionally received financial support from regional and federal governments, the Montreal Olympics were intended to be revenue-neutral and, for that reason, was almost entirely managed by the city.

It was not, however, the media event the Olympics would become in later years. In fact, commercialization was discouraged at Olympics during these years. Whereas broadcasting rights in Montreal sold for approximately $35 million, Moscow raised $80 million in 1980 and Los Angeles raised $287 million in 1984. In 1976, though, the primary sources of revenue were a special lottery and commemorative coins. Nonetheless, the CBC provided an unprecedented amount of coverage – over 175 hours (five times the amount for Munich) – using new colour cameras, remote units and other technology that vastly improved the quality of its reporting. It was so successful that the CBC committed to greater coverage of amateur sports and Olympic events in the future.

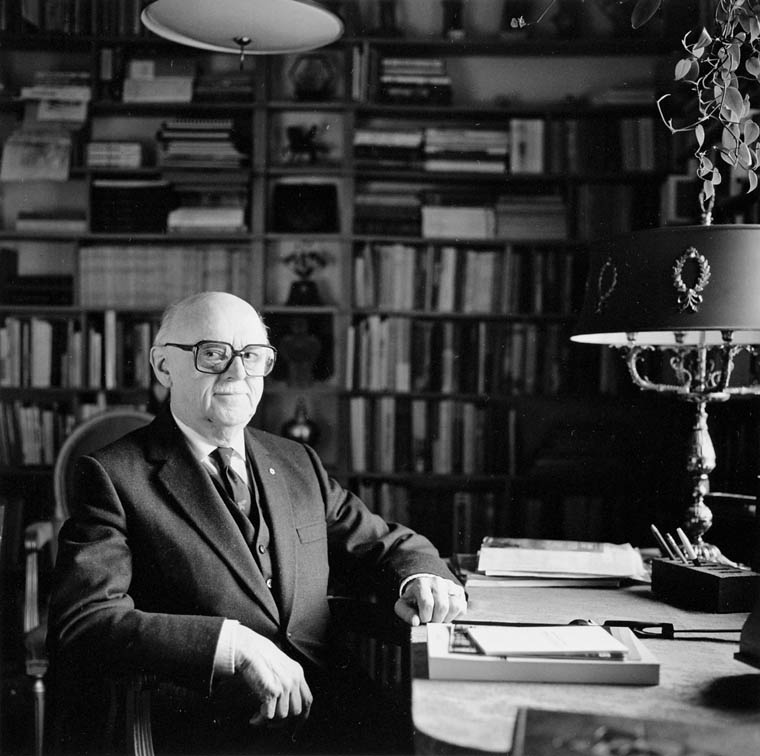

But media coverage was also the cause of intense conflict. Drapeau reneged on his promise to the International Olympic Committee that the latter would retain its monopoly over television rights. The organization was already frustrated with the Munich committee, which had divided media revenue between television rights and technical services (and kept the latter, which amounted to millions of dollars). Montreal’s committee decided to do the same despite earlier assurances to the contrary, which resulted in an unprecedented intervention from the International Olympic Committee’s president, Lord Killanin. Killanin would later write in his memoirs that “the Montreal years, from the time the Canadian city was awarded the games to the XXIst Olympiad until their opening in 1976, were agonizing years for the Movement and, of course, me.”