Security and Olympic Games: Setting the Stage

Security for the Olympics was not a serious preoccupation before Montreal. In 1968, the Mexico City Olympics had been marred by the tragic death of over 300 peaceful student protestors who had been slaughtered by the Mexican army in an attempt to disperse the protest (they were protesting the use of public funds for the Olympics). But terrorism or, in fact, any political violence during an Olympics was unheard of. Security for the Winter Olympics in Sapporo, Japan in 1972 was largely the responsibility of 13,469 local police.

By the 1970s, though, the games were taking place amidst a heightened fear of international and domestic terrorism. National liberation movements spawned terrorist violence across the globe. The Irish Republican Army, Palestinian Liberation Organization, Red Brigade and a host of other terrorist organizations were responsible for bombings, hijacking planes and other acts of violence. It was an era of international terrorism: in seeking targets abroad, they raised the possibility that anyone anywhere could be a target. According to the Global Terrorism Database, there were at least 4340 terrorist attacks between 1970 and 1976 alone. In Canada, the Front de libération du Québec was responsible for numerous bombings, robberies and killings across the Province of Quebec throughout the 1960s. In the United States, there were more incidents of domestic terrorism in the 1970s than any other period in that country’s history: at least 680 incidents compared to 282 in the 1980s (77 fatalities in the 1970s, 22 in the 1980s).

Political violence was gaining greater visibility: incidents of terrorist violence appeared frequently in newspapers and on television. And yet, Olympic organizers did not anticipate a serious terrorist incident in their security planning. The Summer Olympics in Munich in 1972 depended on a modest security force: 10,000 local police officers, 1,147 security service officers, and 883 police from outside Bavaria. Bavaria, which was determined to remove the taint of the 1936 ‘Nazi games’, had insisted on reduced security and local control. Munich organizers had been preoccupied with preventing large scale demonstrations, as had occurred during Mexico games in 1968, and not a serious terrorist threat. Despite intelligence assessments suggesting a possible attack on Israeli athletes, the “police were caught completely off guard, ill prepared, ill equipped and not properly trained to handle such an incident [Source: CHRH Archive].” Terrorists ultimately killed 11 Israeli athletes and one police officer in a fatal shootout at the airport after kidnapping the athletes from the Olympic Village. A Canadian police delegation to Munich following the games concluded that “in the final analysis, security precautions [in Munich] were lax; passes were not checked, persons were not challenged for their identity [Source: CHRH Archive].”

Because of Munich, a highly visible security posture was adopted at the Seventh Asian Games in Tehran and the 1974 World Cup series in West German (both without incident). Munich was also a central preoccupation for the Winter Olympics in February 1976, which was hastily prepared in Innsbruck, Austria after Denver withdrew from hosting. Summer Olympics, however, were far more significant in size, scope and visibility. Montreal was the first Summer Olympics since the Munich massacre, which created a serious challenge for the federal government. Security had not been an integral part of the planning and bidding process, which was almost entirely a local initiative led by Mayor Jean Drapeau and the City of Montreal. The federal government had never wanted the Summer Olympics in Montreal, having already financially supported Montreal’s World’s Fair in 1967 (it was, instead, backing Vancouver’s bid for the Winter Olympics). Prime Minister Pierre Elliot Trudeau was adamant that the federal government would not pay for the games.

Nonetheless, the RCMP warned Cabinet that they could not rely on local police to manage the security operation. Among other reasons, the federal government would invariably be held accountable if there was an incident. Besides, the RCMP alone had the organization and resources to properly plan security for the games. And yet by 1973 there was no security plan. The Montreal organizing committee appeared to be adopting the same philosophy towards security as the Munich organizers, which was of grave concern to the Security Service: “The German experience illustrates dramatically what can occur when constraints are placed on police and security authorities for the sake of an acceptable political image [Source: CHRH Archive].”

The principal lesson from Munich, according to an initial RCMP assessment, was that terrorists did not restrict their activities to domestic targets, but sought to use international events such as the Olympics to seek change at home. The RCMP believed that “the potential for violence at the Olympic games, from any one of several groups that are planning to use this occasion to publicize their causes, continues to be of major concern [Source: CHRH Archive].” The threat from international terrorism was exacerbated by the expansion of air travel. Seventy-two per cent of visitors to the Olympics in Japan in 1964 arrived by plane, and 68 per cent travelled by plane to Mexico in 1968. The RCMP estimated that seventy to eighty per cent of visitors to Montreal would have to be screened at the airport.

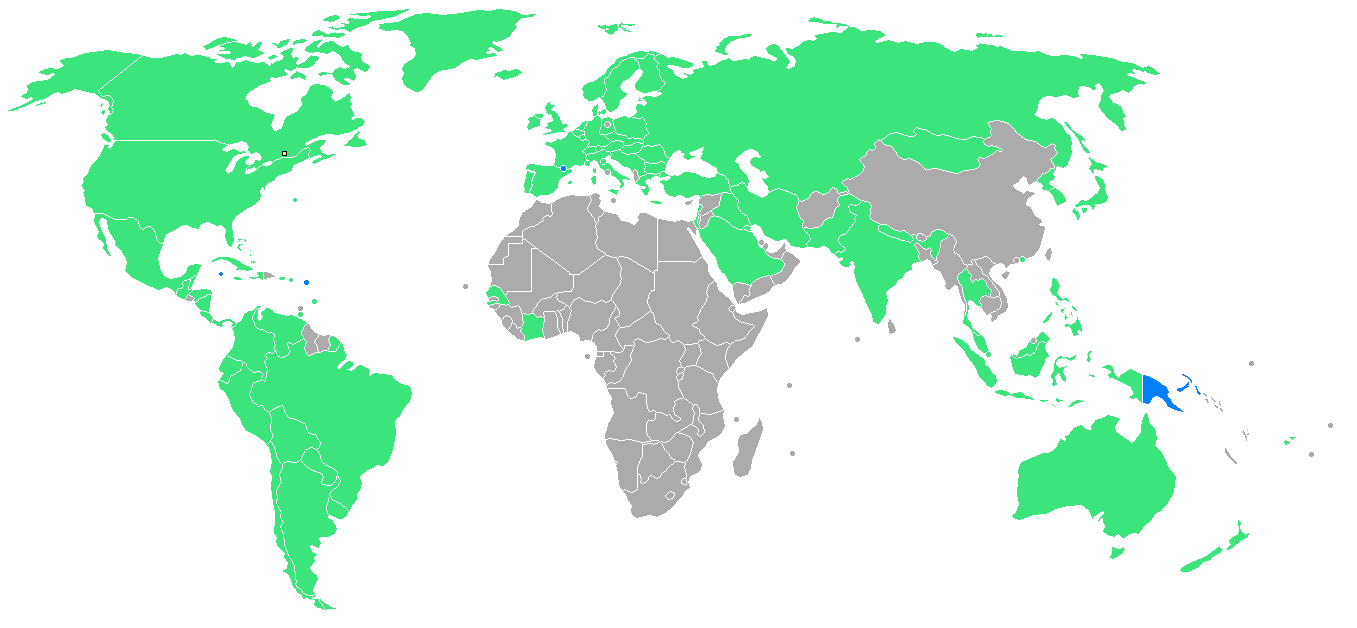

Over five million people would attend the Summer Olympics in Montreal, more than Tokyo in 1964 and Munich in 1972. Six thousand athletes representing ninety-two nations competed in 21 sports. There would also be an unprecedented number of female athletes and new strident doping regulations: at least a dozen athletes were caught using steroids, which contributed to the momentum towards policing steroids in professional sports. Such a massive gathering was bound to strain Canada’s limited security apparatus. It was, in fact, uncommon for such a small country (25 million) to host a Summer Olympics. The security operation, which involved 26 venues, was also divided between several cities: the sailing competitions took place in Kingston while football, archery, pentathlon and equestrian competitions were spread out across a half dozen other cities in the Provinces of Ontario and Quebec. However, there is no evidence in the RCMP’s documents pertaining to the Olympics of any intention to use the games to create a long-term legacy for policing in Canada. Producing a large-scale and technologically sophisticated surveillance state was simply not part of the Security Service’s vision. Still, the federal cabinet had passed an order in council in 1973 that called for a strong security posture for the Olympics. It set the stage for the largest security operation in Canadian history.