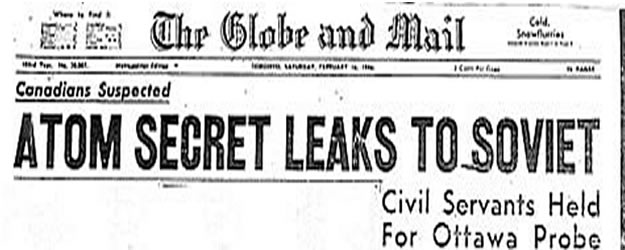

The commission, which investigated cases between 15 February and 15 March 1946, released three interim reports, all of which accused the suspects of sharing classified information with members of the Soviet embassy in Ottawa. The commission dedicated a separate chapter to each suspect, and most chapters ended by accusing him or her of violating the Official Secrets Act (see sentences and report).

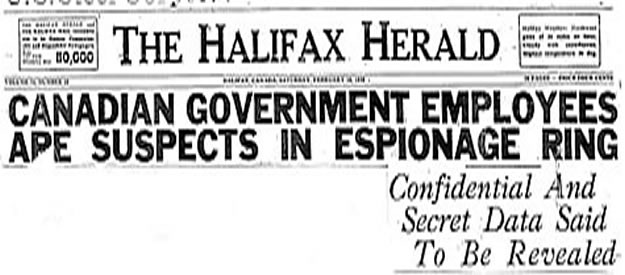

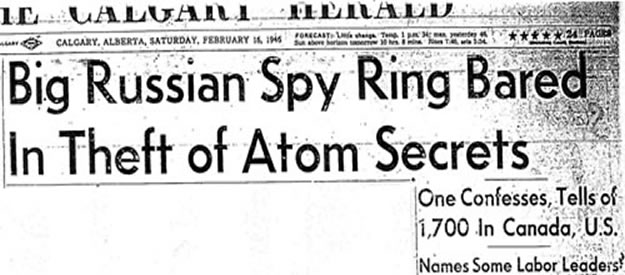

Four suspects were released on 4 March 1946, which coincided with the release of the commission’s first interim report. They were immediately arrested and formally charged with violating the Official Secrets Act (the thirteen people who were detained in February were released in three stages; those who refused to cooperate with the commission were held for the longest time). The so-called spy trials began soon afterward.

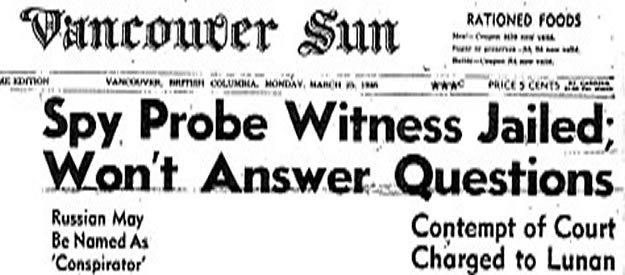

Many of the detainees were deeply scarred by their experience with the commission. One of them, Emma Woikin, was so traumatized by her confinement that when she was finally brought before a judge, all she could do was repeat, in a flat monotone, “I did it … I did it.” Many suspects who agreed to testify before the commission later regretted their decision. Eric Adams, Gordon Lunan, and David Shugar were so disconcerted with the manner in which the commission coerced their confessions that they refused to speak when called as witnesses at other trials (despite having been granted immunity for their testimony against other suspects). As a result, Adams and Lunan were convicted for contempt of court. Their wives attempted to secure their release so that they could meet with their lawyers and prepare for their own forthcoming trials. But the minister of justice, who was not receptive to their pleas, simply stated, “You do appreciate, of course, that it is rather a delicate matter to attempt to interfere with sentences for contempt of Court, but we are giving the matter careful consideration” (see correspondence).

Several suspects also refused to testify as witnesses at the trial of Fred Rose, a member of Parliament and the apparent head of the espionage ring. Ironically, their refusal played a key role in his conviction. When questioned after his trial, one juror stated that “it was not until those four Commies refused to answer questions that we made up our minds and agreed. We knew then that Rose was guilty, and we would have said so had you stopped the trial right then.” (Harvison, The Horsemen). On 27 June 1946, Fred Rose was sentenced to six years in jail. The proceedings of the espionage commission and the subsequent spy trials came to an end soon after with the conviction a few years later of Sam Carr.

Ten of the twenty-three accused were found guilty (see sentences). It is no coincidence that most of those who were acquitted were the last to be released; they had refused to testify before the commission and thus incriminate themselves. Many saw their reputations tarnished or lost their jobs. Despite being acquitted in court, Israel Halperin would have been dismissed from his position as a Queen’s University math professor had its chancellor, Charles Dunning intervened before the board of governors, fearing embarrassment to Queen’s if Halperin were fired. Another acquitted suspect, David Shugar, lost his position with the Department of National Health and Welfare.

The commissioners (Supreme Court justices Roy Lindsay Kellock and Robert Taschereau) were censured for employing extreme tactics. Civil libertarians and the press were critical of the government’s decision to use the War Measures Act to detain a group of people incommunicado while a royal commission interrogated them (civil liberties groups’ response). Nonetheless, the government acted within the scope of the law. To understand how a government could arrest more than a dozen people for an indefinite period of time, hold them incommunicado, and interrogate them without benefit of legal counsel, it is important to examine the three statutes that guided the commission’s actions: Official Secrets Act, Inquiries Act, and War Measures Act.