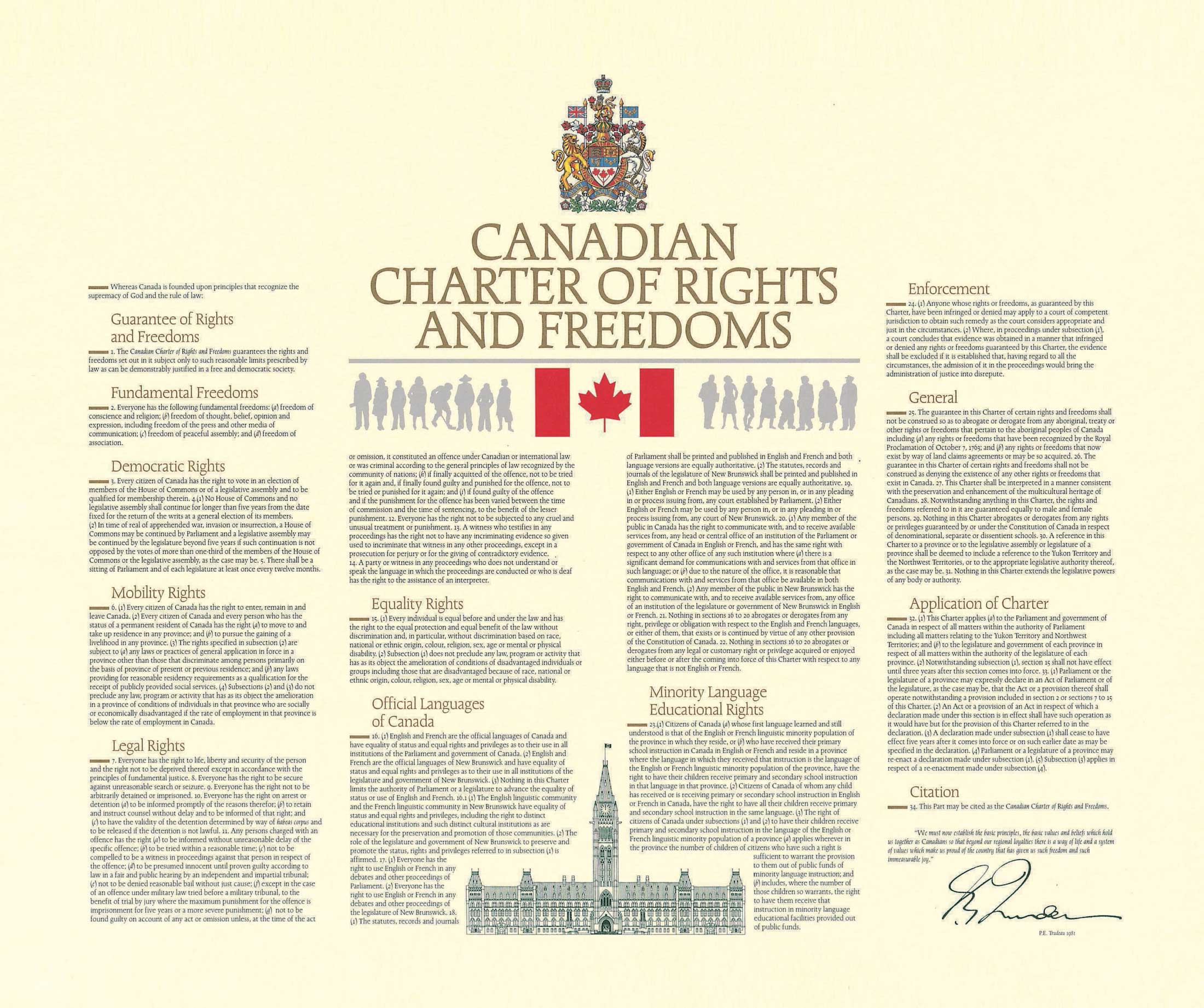

Human rights legislation was far from perfect, however. Discrimination against people with disabilities was not banned until the 1980s, and many provinces refused to recognize sexual orientation until the late 1990s. Whether or not Aboriginal people were adequately protected under human rights law was another complication. Under the federal Human Rights Act, Aboriginal people on reserves were not permitted to submit complaints, though they could, and did, submit complaints under provincial statutes for racial discrimination. Other deficiencies with human rights law were common across Canada. Fines were modest, often between $500 and $1,000. Only Quebec’s legislation recognized economic, social, and cultural rights. Quebec was also the only jurisdiction where commissioners were appointed directly by the National Assembly, which assured a greater degree of independence and job security. Other statutes empowered cabinet to appoint commissioners, and except in Quebec and federally, they held their positions at the discretion of the minister. Moreover, many of the first human rights laws included exemptions for charitable, philanthropic, or religious institutions, as well as major employers and service providers such as educational institutions. These exemptions later became the source of intense controversy. In Newfoundland, for instance, Christian churches monopolized the education system, and their refusal to hire people outside their faith or to allow non-Christians to be elected to local school boards clearly violated the spirit of the law. These exemptions also had a particular impact on women. Kimberly Nixon was refused permission to volunteer as a peer counsellor at Vancouver Rape Relief in 1995 because she was born male. The British Columbia Human Rights Tribunal ruled that Rape Relief’s action constituted sex discrimination. But the BC Supreme Court overturned the tribunal’s decision and determined that the service was a legitimate exemption to the legislation.

Still, it is difficult to overstate the historical significance of human rights legislation. Human Rights Commissions were more efficient, faster, and accessible than the courts. They bore the cost of investigating and resolving conflicts. Human rights adjudication was also more accessible than the courts. Specially trained human rights officers investigated complaints, and the staff of Human Rights Commissions were drawn from academia, the media, social activists, churches, and the legal community. By incorporating existing legislation into a single statute, and developing experts in the field of human rights, the state accepted (to a degree) that discrimination was a systemic social problem. Significant resources were provided for most human rights adjudication, and each commission had a mandate to educate the public and to recommend future legislative reform to the government. Invariably, with a dedicated bureaucracy and a mandate to educate and promote human rights, the numbers of complaints would have a snowball effect, particularly as citizens became aware of the commission and would not face the financial hardships commonly associated with litigation.

A genuine rights revolution had occurred in Canadian law.