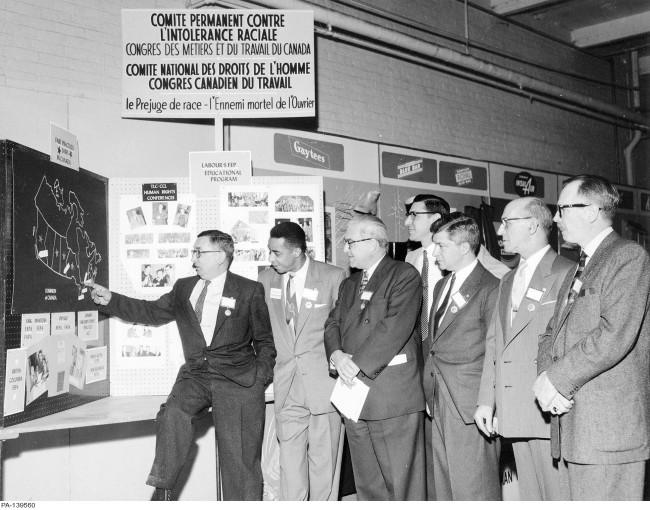

With the support of organized labour, the Jewish Labour Committee and its leader, Kalmen Kaplansky, were at the forefront of the campaign for anti-discrimination legislation in Canada. Kaplansky was adept at raising funds and overcoming divisions within the labour movement. By the 1950s, a coordinated national strategy was in place, and it produced tangible results. The federal government introduced a fair employment practices law in 1953 and added an anti-discrimination provision to the National Housing Act in 1960, largely in response to labour movement lobbying. The New Brunswick government enacted fair employment practices legislation in 1959, less than a year after the provincial federation of labour began to lobby for anti-discrimination legislation. Successive Quebec governments had resisted implementing anti-discrimination laws, but thanks to the efforts of the Montreal JLC committee (the United Council for Human Rights) and the Quebec Federation of Labour, the provincial government passed An Act Respecting Discrimination in Employment in 1964. In a brief to the Quebec premier, the JLC claimed the support of forty social movement organizations representing unions, churches, Jews, students, ethnic minorities, women, and prisoners. Ottawa’s first anti-discrimination legislation, in 1952, was largely the product of a campaign by organized labour and its allies in Parliament. In Nova Scotia and Saskatchewan, municipal labour councils, provincial labour federations, and the JLC worked closely to secure anti-discrimination legislation and to improve existing legislation (the Halifax Human Rights Advisory Committee and the Nova Scotia Association for the Advancement of Coloured People were also part of the campaign). If fair employment practices legislation already existed, organizations such as the British Columbia Federation of Labour or the Toronto Labour Committee for Human Rights lobbied for fair accommodations practices legislation. As the federal Department of Labour acknowledged, “it can be stated without qualification that the history of fair employment practices legislation in Canada testifies to the effectiveness of the fundamental educational groundwork carried on by labour.” [Clément 2014]

Unlike the Saskatchewan Bill of Rights, fair employment and practices statutes were based on an administrative (not criminal) model. They empowered a minister (usually the minister of labour) to appoint an investigator, and if necessary, the minister could appoint an independent ad hoc commission to consider the case and recommend a remedy (such as a fine or an offer of employment). Complainants did not have to resort to the courts, and the administrative apparatus favoured an initial attempt at conciliation rather than direct confrontation. For the complainants, this model had the added benefit of placing the burden of investigation on state officials, rather than requiring that they themselves hire (and pay) their own lawyers and investigators, as most did not have the resources to pursue complaints on their own. The administrative model required them to prove a balance of probabilities of guilt, not guilt beyond a reasonable doubt, the more demanding standard of criminal proceedings. If, however, the complainant continued to face discrimination, the case would be referred to the courts. In this instance, the burden of proof was more stringent, and the complainant would receive no remedy (court-imposed fines were collected by the government).

For these reasons, anti-discrimination laws were ineffective. Of the 502 complaints received between 1951 and 1962, only 1 was successfully prosecuted under Ontario’s Fair Accommodation Practices Act (Morley McKay, the racist owner of an Ontario cafe, was fined $25 and an additional $155 for costs in 1955). The number of complaints investigated in other jurisdictions from the mid-1950s to the late 1960s was a fraction of those received in Ontario: Manitoba (2), New Brunswick (15), Quebec (24), and Saskatchewan (30). The federal legislation also went largely unused: only thirty people sought relief under the law between 1953 and 1960.

The failure of early anti-discrimination measures is easy to explain. The legislation was unwieldy and difficult to enforce. Discrimination was notoriously hard to prove. Responsibility for enforcing the law was hoisted onto the shoulders of civil servants who had no expertise, and often little interest, in the issue. Governments were unwilling to dedicate the necessary resources to enforce the legislation. Moreover, with no budget for education or promotion, it is likely that few people were even aware that the law existed.

The 1960 case of Gerri Sylvia, a young black woman living in Winnipeg, exemplified the failure of such laws. After a year of struggling to find work as a waitress, she picked up the phone and called David Orlikow. An NDP member of the Manitoba Legislative Assembly, he was the secretary for the local Joint Labour Committee to Combat Racial Discrimination (and, later, national director of the JLC). Orlikow drove around the city with Sylvia, and as he waited in the car, she walked into Hilton Restaurant, Raphael’s Restaurant, South Seas Restaurant, and Zoratti’s Restaurant to apply for jobs that had been advertised in the newspaper. Her applications were quickly rejected, and in some instances, no one even bothered to ask about her qualifications. The next day, Orlikow sent two white women to the same restaurants to apply for the same jobs. They were promptly offered the positions. Orlikow brought the case to the provincial minister of labour, who appointed a commission under the Fair Employment Practices Act. After numerous delays, the commission dismissed the case on a technicality. In addition to citing lack of evidence, the inquiry’s chairman, G.F.D. Bond, insisted that Sylvia was not looking for work, only investigating whether the restaurants practised discrimination, and thus was not genuinely denied employment (Sylvia had filed a complaint in the previous year after ten cafes refused to hire her, but that complaint was dismissed without an inquiry due to lack of evidence).