Human rights, as many historians have argued, “played virtually no role as a protest language in the decades after the Second World War.” Not until the 1970s did human rights become an integral component of international politics. Amnesty International symbolized this new era. Membership in AI expanded dramatically, from 20,000 in 1969 to 570,000 in 1983. Also, the organization shed its earlier focus on prisoners of conscience to become a truly human rights association addressing a range of violations.

Among the most visible human rights campaigns were those in Eastern Europe and South America. One of AI’s first and most successful campaigns was against Augusto Pinochet’s brutal dictatorship in Chile (1973– 89). After overthrowing Salvador Allende, the military junta imposed a state of terror that included eliminating political opponents, engaging in torture and indiscriminate killings, banning political parties and trade unions, and censoring the media. Chile, much like Argentina, adopted a practice of “disappearances”: the intelligence services would kidnap people, deny that they were incarcerated, and dispose of the victim’s bodies (sometimes by throwing them out of planes into the ocean) to conceal the evidence. One of the more gruesome practices of the Argentinian regime involved imprisoning pregnant women until they gave birth; then, after killing the mother and disposing of her body, the state would give the baby to a couple seeking adoption. The prison guards were, in essence, feeding a pregnant woman to keep her alive until they could harvest her offspring. Although AI and its network of transnational human rights organizations failed to undermine the regime in Chile, it did much to foster international condemnation of it. Later, in the 1980s, AI would play a critical role in undermining Argentina’s junta.

There had been international human rights movements before this— most notably, the antislavery and suffragette movements. But the 1970s saw the birth of a truly transnational human rights movement. By gathering information and leveraging countries against one another, newly emerging transnational networks brought pressure to bear against apartheid in South Africa, disappearances in Chile and Argentina, Indonesia’s oppression of the East Timorese, and the suppression of political dissent in the Soviet Union and the Philippines. By drawing attention to horrific narratives of torture, killings, and imprisonments, AI and various transnational advocacy networks inaugurated a new era of global human rights politics.

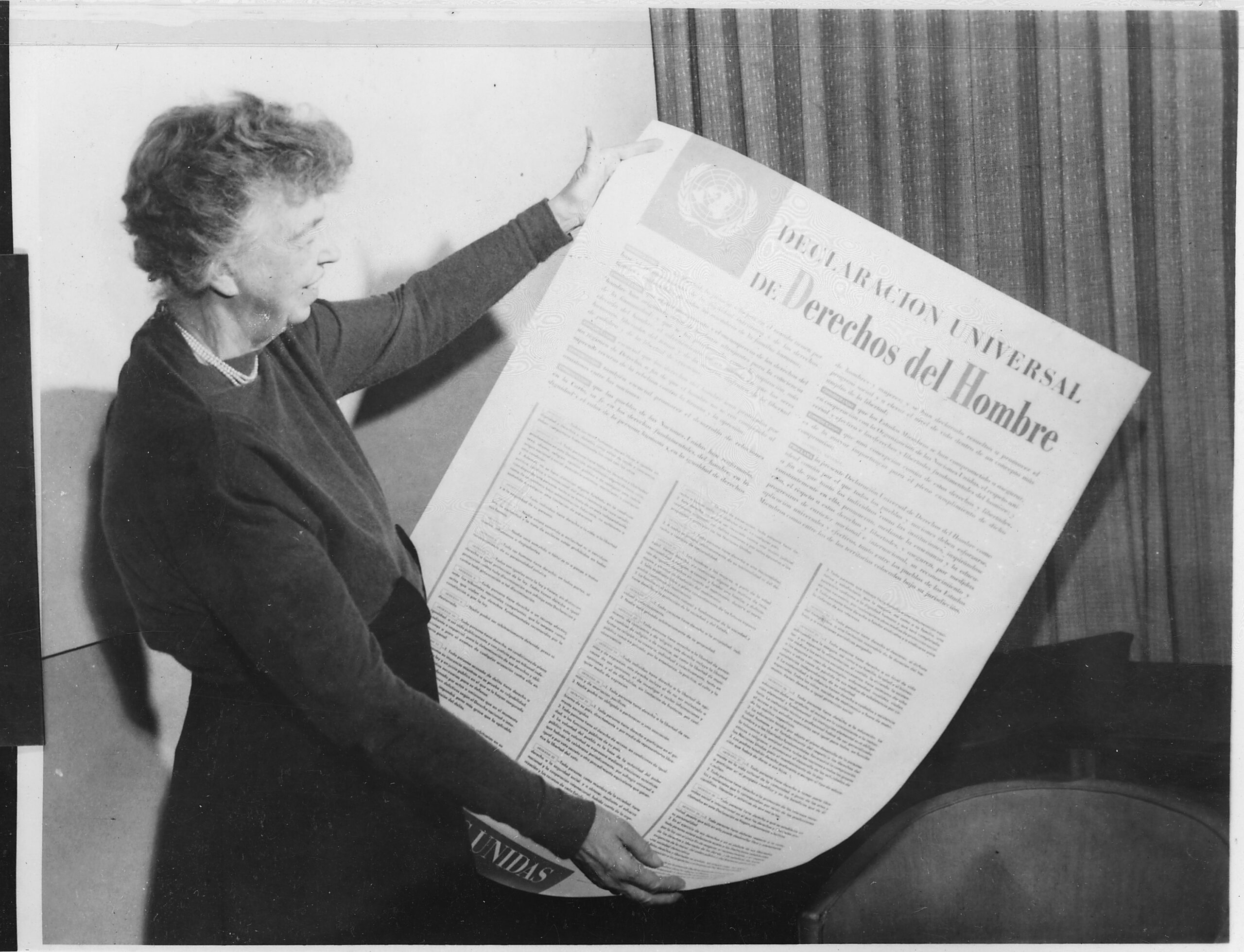

It was also during this period that the modern international human rights regime was born. Many of today’s “core” human rights treaties came into force during this period: the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racism (1969); the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (1976); the International Covenant on Social, Economic and Cultural Rights (1976); the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (1981); and the Convention Against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (1987). Ratification of these treaties had increased exponentially by the 1980s. In 1948, most states had questioned the legitimacy of the UDHR; by the 1980s, it had become almost compulsory for any liberal state to ratify a human rights treaty.

It was almost inevitable, given such developments, that Canadian foreign policy would begin to incorporate human rights. In 1975, the federal government established a Federal/Provincial/Territorial Continuing Committee of Officials on Human Rights to consult over international treaties. After securing provincial consent, Canada in 1976 acceded to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, as well as the International Covenant on Social, Economic and Cultural Rights. Canada later supported declarations or conventions relating to racism, children, and women’s rights. This meant that officials had to prepare speeches for ministers commemorating anniversaries or special human rights initiatives, and officials from the Department of External Affairs had to meet with human rights SMOs regularly to prepare for UN Commission on Human Rights meetings. Canada demonstrated its commitment to promoting human rights abroad through interventions in sessions of the Commission on Human Rights and similar international forums. Canadians also played a key role in drafting the Declaration on the Elimination of All Forms of Intolerance and Discrimination Based on Religious Belief (1981). These initiatives indicated a profound shift in foreign policy, which in the past had rejected human rights as a legitimate component of international politics.

Canada participated in the negotiations that led to the Helsinki Accords in 1975 with the Soviet Union. Among other things, those accords committed each country to a set of human rights principles. These international commitments provided a unique opportunity for parliamentarians to involve themselves in foreign affairs. Before this, MPs had responded to human rights violations in Eastern Europe with vague calls for self-determination or minority rights. Now, MPs were able to draw on the language contained in the Helsinki Accords to introduce resolutions in Parliament dealing with family reunification, free movement of people, religious freedom, and other equally precise reforms that demonstrated an evolving understanding of the issues. MPs also participated in increasing numbers in international human rights conferences as part of Canadian delegations to the UN and as members of various monitoring groups abroad. Over time, many MPs gained valuable experience and expertise on human rights issues, and they brought this knowledge to Parliament, where they continued to pressure the federal government to integrate human rights into foreign policy. A private member’s bill was introduced in 1978 to prohibit foreign aid to countries with poor human rights records. Although the federal government immediately rejected the idea, the bill remained on Parliament’s agenda, where it drew attention to the human rights component of Canadian foreign policy. As a result, the government was forced to defend and elaborate its aid policies in public.

There were also many instances when international developments had an impact on domestic policy. Among other things, policy-makers could appeal to international human rights law when implementing controversial domestic legislation. The International Year for Human Rights, besides facilitating the emergence of numerous human rights organizations, was the impetus for human rights legislation in British Columbia, Alberta, New Brunswick, and Newfoundland. Political leaders often cited international human rights treaties when justifying the introduction of human rights laws, including the federal Bill of Rights (1960), the Ontario Human Rights Code (1962), the Quebec Charter of Human Rights and Freedoms (1975), and the Yukon Human Rights Act (1987). British Columbia would use the International Year of the Disabled as an incentive to ban discrimination on the basis of physical and mental disability. And most of the provinces introduced legislative reforms in response to Canada’s acceding to the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women.