The Special Joint Committee on the Constitution was another critical moment in Canada’s human rights history. The hearings highlighted a host of new rights claims; they also demonstrated how Canadians were building on earlier claims. After their success in the 1970s in banning direct forms of sex discrimination, especially in the workplace, women now put forward rights claims on a number of other issues, from abortion to day care. Of course, women had been mobilizing around these issues for generations. But it was indicative of the impact of the rights revolution that they were now framing their demands in the language of human rights.

But it was Indigenous peoples who provided the most impactful moments during the hearings. Indigenous peoples’ organizations had never before engaged with human rights policy in a meaningful way. True, they had participated in public discussions surrounding the federal Human Rights Act, but only to oppose any provisions that might apply to the Indian Act. Most Indigenous peoples’ organizations insisted on completing negotiations over outstanding claims before addressing human rights legislation. Complaints to human rights commissions involving Indigenous peoples had always been few in number: a survey of complaint files in British Columbia, Alberta, Ontario, New Brunswick, and Newfoundland reveals that by 1982, human rights commissions had rarely investigated complaints involving Indigenous peoples. One of the most widespread consultations on human rights law in the 1970s, the Ontario Human Rights Commission review titled “Life Together,” received few briefs or letters from Aboriginal organizations. Indigenous peoples’ refusal to engage with human rights policy may also have been due to the lack of any cultural tradition of rights. To be sure, Indigenous peoples had legitimate reasons to be skeptical of the benefits of framing their issues using rights language following the debacle over the 1969 White Paper. And for obvious reasons, most Indigenous mistrusted government agencies.

Nonetheless, several Indigenous peoples’ organizations participated in the hearings. The Association of Métis and Non-Status Indians of Saskatchewan drew attention to the deplorable living conditions on reserves and demanded recognition of Indigenous peoples’ right to control natural resources, economic development, and education. The National Indian Brotherhood framed their exclusion from political life as a form of collective discrimination, while insisting on hunting rights and a repeal of the ban against ceremonies. Human rights, they insisted, had to include self-determination and a positive recognition of treaties.

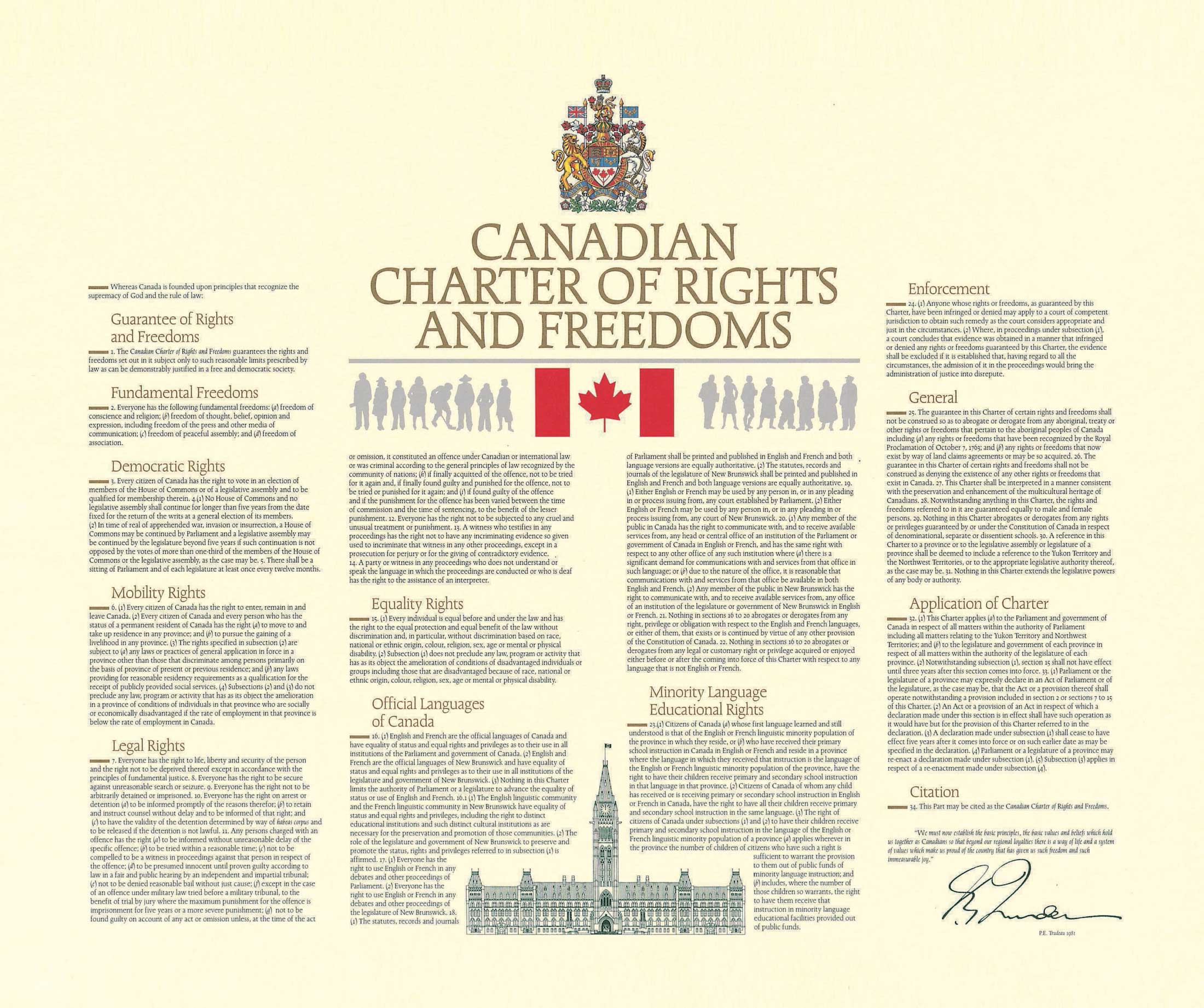

Social movements had a considerable impact on the Charter. Indigenous peoples’ organizations secured a section on Indigenous rights, while women’s groups led an impressive campaign to save the equality section. French and English language rights associations provided important rhetorical support for entrenching minority language rights in the constitution. Civil liberties groups, lawyers’ associations, and human rights commissions had a direct impact on the wording of several sections. One of the first concerted campaigns by people with disabilities resulted in an explicit reference to their equality rights, while ethnic minorities’ efforts resulted in a section on multiculturalism. Public discourse surrounding human rights in the 1950s had been dominated by references to civil liberties (speech, association, assembly, press, religion, due process, and voting) and to racial, religious, or ethnic discrimination; the Charter debates revealed how Canada’s rights culture had evolved and how social movements were continuing to push at the boundaries.

Canada became the first country to recognize multiculturalism in its constitution and one of the few in the world with a bill of rights incorporating education, language, Indigenous peoples, and equality between men and women.