In 7 August 1971, prompted by articles in the Georgia Straight, an alternative newspaper, hundreds of young people converged on Maple Tree Square in Vancouver’s popular Gastown area. For the previous week, Georgia Straight writers Kenneth Lester and Eric Sommer had been promoting the gathering to protest drug laws and recent drug raids in Vancouver (Operation Dustpan). Hundreds of young people, many described by the media as hippies, assembled in the square; some were smoking pot, others playing music or just wandering around. By ten in the morning, their numbers had reached almost two thousand. Inspector Abercrombie, who was the senior police officer in charge at the scene, decided to clear the crowd after receiving false reports that windows had been broken. He ordered everyone to leave within two minutes. When this was ignored, he instructed four mounted officers to disperse the throng. They were followed by police in riot gear who were supported by plainclothes officers scattered among the crowd. Pandemonium ensued. Innocent bystanders found themselves caught up in a battle between police and youth, some of whom threw rocks, chunks of cement, and bottles. Abercrombie quickly realized that he was faced with a riot.

A Vancouver Sun article of 9 August 1971 examined police reports and reconstructed some of the incidents that occurred after Abercrombie gave the order to clear the street:

- Police officers on horseback drive people into doorways and pin them there while lashing at them with their riot sticks.

- Held by the hair and one arm, a screaming young woman is dragged for about a hundred yards over broken glass by two police officers, who take her to a waiting paddy wagon.

- A large chunk of cement strikes a policeman just below his right knee. The crowd jeers as he staggers.

- A young woman marches toward a group of officers and shouts, “You might as well take me too.” They comply. As they shove her into the wagon, bent over so that she almost touches her toes, an officer shoves his riot stick into her seat, pushing her inside.

- Cut down by a blow from a riot stick, a young man slumps on the street. A weeping young woman kneels beside him.

- Another youth is held down in a parking lot, where he is struck three times by a policeman’s stick. Another boy, his head bound with a bloody bandage, is loaded into an ambulance.

- A bottle sails out of the crowd and shatters between an officer’s legs. He sprints into the crowd and raises his stick but does not strike.

- A man approaches an officer in the police line and asks permission to go by because he has lost his wife. He is allowed to pass.

- An elderly Chinese woman picks vegetables out of the shattered plate glass from her grocery store window.

- Mounted officers gallop down sidewalks filled with pedestrians, scattering them in all directions.

- Gangs of youths roam the streets within six blocks of Maple Tree Square, throwing rocks and bottles at police.

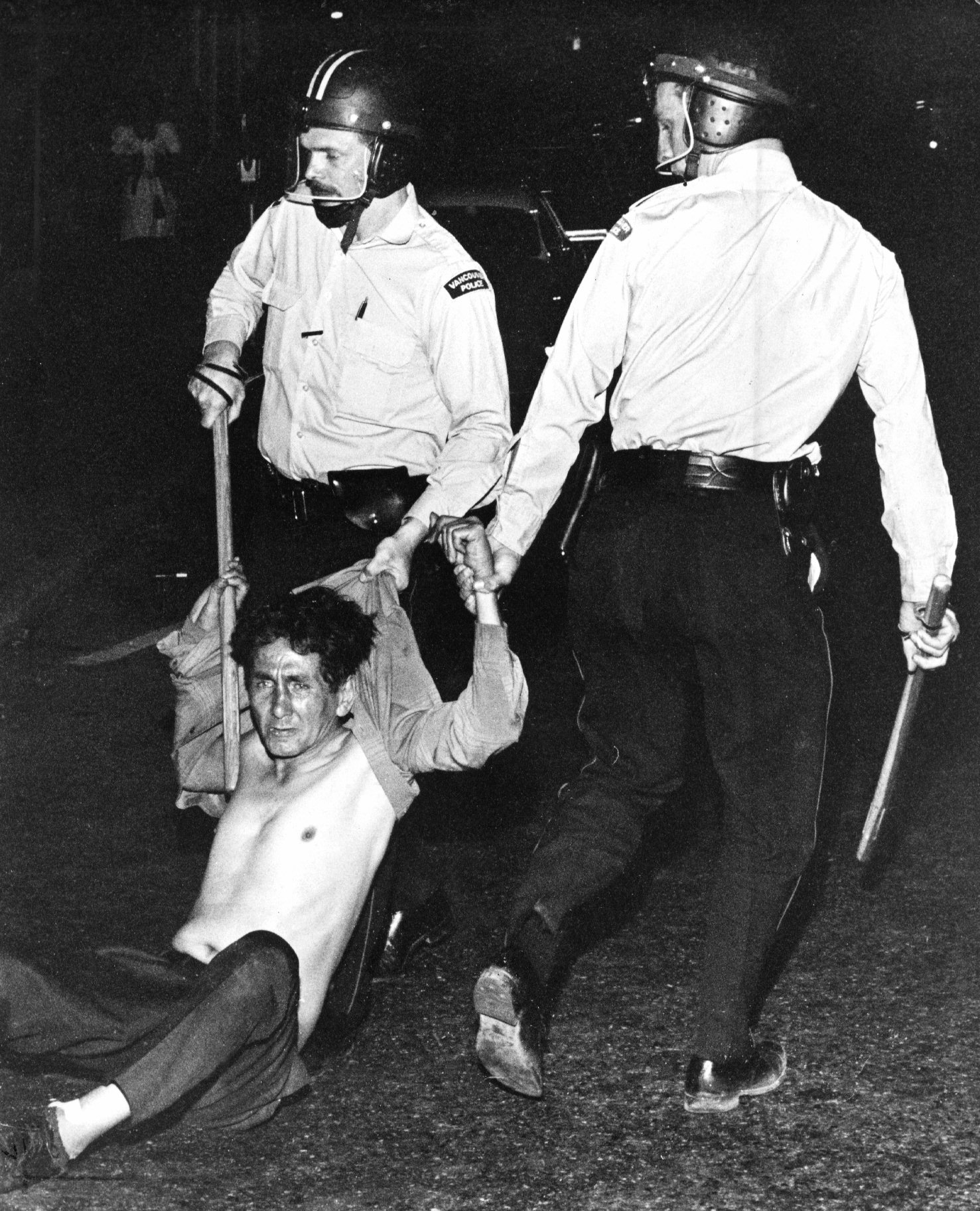

- Youths and adult men and women are dragged into paddy wagons.

- The police wear no badges or identifying numbers on their uniforms.

- Numerous groups of young people shout obscenities.

- Police enter shops and restaurants to grab people who have taken refuge from the chaos in the streets.

- Several plate-glass windows are smashed in stores.

- Pools of blood lie in several places throughout Gastown.

- Riot-equipped police stand guard outside the public entrance to the police station at 312 Main.

Seventy-nine people were arrested and thirty-eight were charged with various offences. There was an immediate public backlash, and newspapers filled their front pages with details on the riot and its aftermath. The Vancouver Sun called for an inquiry, noting that the “volume of rhetoric and abuse that has been pouring out ever since [the riot] … has so confused the public that only a detached, impartial and coherent assessment of the whole affair will now suffice to put blame where it belongs.” [12 August 1971] The Vancouver Province was convinced that there would be “deepening suspicion and hostility between young people and the police – unless Attorney General Peterson steps in at once and orders an independent investigation of the whole affair.” [10 August 1971] Naturally, the Georgia Straight was quick to condemn the police and point to the riot as proof that the police force was hostile to young people. Vancouver mayor Tom Campbell defended the police and claimed that a conspiracy by Sommer and Lester was responsible for the violence; however, he publicly stated his support for an inquiry into alleged police abuses. Gastown merchants, sympathetic with those caught in the riot, organized a bail fund and planned a social gathering for protesters and police to ease tensions in the community. In late August, the attorney general ordered Thomas Dohm (a BC Supreme Court judge) to investigate the causes of the Gastown Riot.

The Dohm inquiry lasted for ten days and heard forty-eight witnesses. Justice Dohm acknowledged that Abercrombie had been overzealous, and he agreed that the crowd had not degenerated into a mob and that individual officers used “unnecessary, unwarranted and excessive force.” [British Columbia, Report on the Gastown Riot] His recommendations to the Board of Police Commissioners included banning demonstrators from taking over public streets, training squads of police officers specifically for crowd control duty, using horses for crowd control except on sidewalks and at storefronts, and eliminating the use of plainclothes officers for crowd control. In addition, Dohm placed responsibility for the riot squarely on the shoulders of Sommer and Lester, whose “true motivation is their desire to challenge authority in every way possible … Any popular cause serves their purpose if it enables them to gather a gullible crowd who may act in such a way as to defy any authority. The harassment of young people by the drug squad police and the resultant hostility was grist to their trouble-brewing mill.” Dohm, Mayor Campbell, and George Murray of the police union all blamed the riot on an anarchist conspiracy to cause havoc on the streets. The Vancouver Province concluded that the “root cause of the whole ugly business” was “two dangerous yippies [who were trying] to use a protest against marijuana law as a means of gathering a crowd for a confrontation with police.” This sentiment was shared by the Vancouver Sun, which, though it lambasted Campbell for his inflammatory rhetoric, blamed a small group of troublemakers for the riot. The BC Civil Liberties Association and other advocacy groups sought a deeper explanation. They pointed to the underlying friction between the youth protest movements, with their illicit drug use and hippie culture, and the attitudes of the state and media regarding them.

Source: Vancouver Archives

Further Reading

- British Columbia. Report on the Gastown Riot. 1971.

- Campbell, Lara, Dominique Clément, and Greg Kealey, eds. Debating Dissent: Canada and the Sixties. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2011.

- Clément, Dominique. Canada’s Rights Revolution: Social Movements and Social Change, 1937-82. Vancouver: UBC Press, 2008.