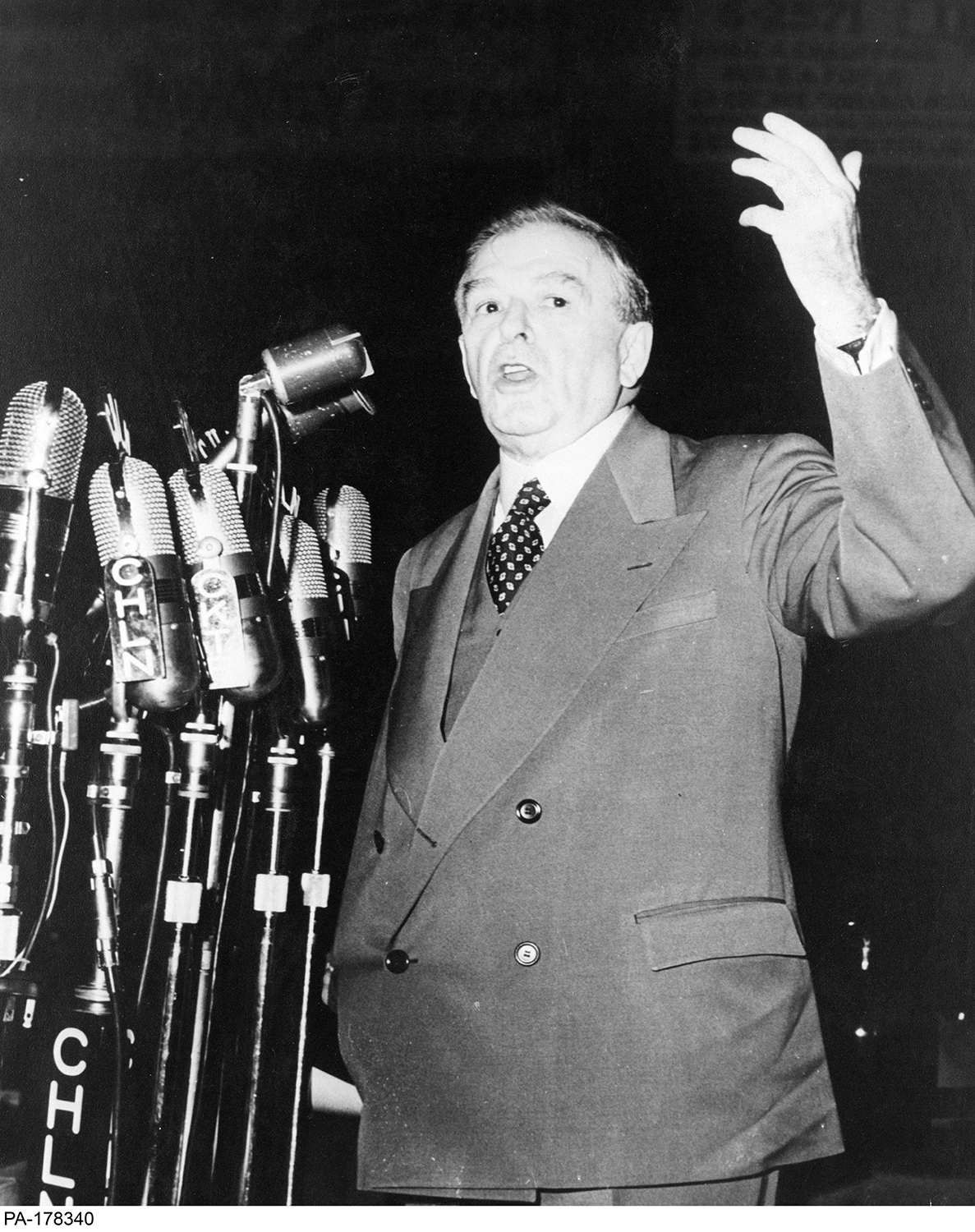

In 1936, the federal government revoked section 98 of the Criminal Code, a move that prompted Quebec premier Maurice Duplessis to create An Act to Protect the Province Against Communistic Propaganda, nicknamed the Padlock Act, in 1937. The act was inspired by section 98, which had been introduced in 1919, following the Winnipeg General Strike of that year. Section 98 empowered the federal government to deport non-citizens and to charge individuals with criminal conspiracy for threatening the social order or promoting revolution. The Padlock Act enabled local sheriffs (under the authority of the Quebec attorney general) to close down the meeting places of those who were suspected of endorsing “communism” or “bolshevism,” terms that the statute did not define. The act’s nickname refers to the practice of padlocking the door to prevent use of the building. Although an order could be challenged in court, this was extremely difficult to do, which ultimately meant that the courts could not check the powers of the attorney general under the Padlock Act. The powers of the act were so widespread that it was used to persecute Jehovah’s Witnesses, Jews, communists, trade unionists, and anyone who was suspected of subversion. It became a rallying point for civil libertarians, who considered it one of the most repressive laws in Canadian history.

As Ross Lambertson notes in Repression and Resistance, the act contained numerous opportunities for abuse:

“Should the attorney general (who was also the premier) be satisfied that a house had been used illegally in this fashion, the legislation gave him the power to ‘order the closing of the house for any purpose whatsoever for a period of not more than one year.’ In other words, the police could padlock the house, apartment, or place of business without the necessity of formally laying charges or bringing anyone to trial. The legislation did permit the owner of a padlocked property to petition the courts for a cancellation or suspension of the order, but the burden of proof was upon the owner to demonstrate that the property had not been used, or was used without the owner’s knowledge, as a place from which Communist propaganda was being spread. (As Eugene Forsey wrote at the time, this was ‘contrary to every principle of British justice,’ because the property owner was ‘assumed to be guilty until he can prove himself innocent!’) The law also made it unlawful, with a punishment of imprisonment lasting from three to twelve months, ‘to print, to publish … or to distribute in the province any newspaper, periodical, pamphlet, circular, document or writing whatsoever propagating or tending to propagate Communism or Bolshevism.’ Moreover, Duplessis could also empower the police to seize, confiscate, and destroy any such materials. In later years Eugene Forsey, who became one of the most outspoken opponents of the Padlock Law, recalled that from the beginning it had been popular with Quebec’s political establishment, and not just those in the Union Nationale … It imposed censorship on a political party which, however controversial, was perfectly legal in Canada now that section 98 of the Criminal Code had been repealed. Second, this censorship could be executed at the whim of the premier, thereby raising the spectre of ‘executive despotism.’ And third, it attacked the property rights not only of Communists but also of non-Communists who had (perhaps even inadvertently) rented or leased their property to a person distributing propaganda or even holding a radical meeting. One of the forgotten victims of the Padlock Law was an instalment furniture company which was able to repossess its furniture from a padlocked home only two years after the police had applied their padlock. Yet there was more. The statute contained no definition of the term ‘communism.’ As R.L. Calder put it, ‘the definition of Communism reposed in the cranium of the Attorney-General,’ and Duplessis was capable of considering almost any critic a Communist. Indeed, one of his cabinet ministers argued that the law was explicitly ‘aimed at the many people who are Communists without knowing it.’ This gave the authorities carte blanche to decide what forms of unpopular political dissent could be suppressed, and in practice it meant the seizure of any writings that the police suspected might be left wing. In addition, it was almost impossible to launch a court challenge to the padlocking of a property or the seizure of materials.”

The Padlock Act was finally challenged in the Supreme Court of Canada in 1957. The only issue for the court was whether or not it fell within the jurisdiction of the province. The majority of the nine judges found the act to be criminal law and thus ultra vires – beyond the jurisdiction of the Quebec legislature (Switzman v. Elbling). Ivan Rand and several other justices chose to comment on the validity of the provincial claim to have powers under “Property and Civil Rights” for limiting a fundamental freedom. According to Rand, for “the past century and a half in both the United Kingdom and Canada, there has been a steady removal of restraints on this freedom [of expression] stopping only at perimeters where the foundation of the freedom itself is threatened.” He added that freedom of expression had “a unity of interest and significance extending equally to every part of the Dominion.” Justices Fauteux and Abbot insisted on constraining the provinces’ ability to legislate against freedom of expression. Abbot claimed that no province could violate a freedom that was necessary for the continued viability of Canadian democracy. Their decision may not have established a precedent for protecting freedom of speech, but it did eliminate one of the most draconian laws ever passed in Canada.

Further Reading

- Berger, Thomas. Fragile Freedoms: Human Rights and Dissent in Canada. Toronto: Clarke-Irwin, 1981.

- Lambertson, Ross. Repression and Resistance: Canadian Human Rights Activists, 1930-1960. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2004.

- Scott, Frank R. Civil Liberties and Canadian Federalism. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1959.

- Tarnopolsky, Walter. The Canadian Bill of Rights. Toronto: Carswell, 1966.