Canada accepted some minor international human rights obligations in the first half of the twentieth century: Canadians attended the Paris Peace Conference in 1919, signed the Treaty of Versailles, and joined the League of Nations. But Canada was hardly committed to advancing human rights abroad. As John Humphrey, the Canadian who helped draft the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, noted in 1948: “I knew that the international promotion of human rights had no priority in Canadian foreign policy.”

It is a historical irony that, in the same year it was denying due process to suspected spies and disenfranchising Japanese Canadians, the federal government received word from San Francisco that the UN was drafting a Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR). The UDHR raised serious concerns in Canada, especially among the Canadian Bar Association and leading members of the federal Cabinet. Pressure from its allies—and the distasteful possibility of voting alongside South Africa, Saudi Arabia, and the Communist Bloc—forced Canada to support the UDHR in the final vote in 1948. However, Canada joined South Africa, Britain, Australia, and the United States in demanding a domestic jurisdiction clause to prevent the UN from intervening in domestic affairs. Officially, the federal government insisted that it was concerned about violating provincial jurisdiction. Privately, the prime minister was far more apprehensive that the declaration could be used “to provoke contentious even if unfair criticism of the Government.” History would prove him correct.

As of 1962 the federal government had yet to embrace human rights as a foreign policy priority. Canada had gone so far as to cite the principle of state sovereignty in opposing intervention over gross human rights abuses in South Africa in 1955 (and, later, in Nigeria in 1968). The terms “human rights” and “civil liberties” do not appear once in the publication Documents in External Relations for the period between 1946 and 1960. “The early Canadian attitude toward United Nations involvement with rights,” explains Cathal Nolan, “was clearly apathetic, and even a little smug. Ottawa considered the US proposal on human rights wrongheaded at best, and at worst as constituting an invalid interference in the internal affairs of states.” Canadian foreign policy privileged state sovereignty to the detriment of human rights intervention. The country’s support for human rights, especially within the UN, was initially based on a cold calculation of self-interest: “Ottawa slowly accepted an international dimension to rights because it came to believe that the popular appeal of the idea might help keep afloat the UN and thereby the promise of security that multilateral statecraft was thought yet to carry in its hold.”

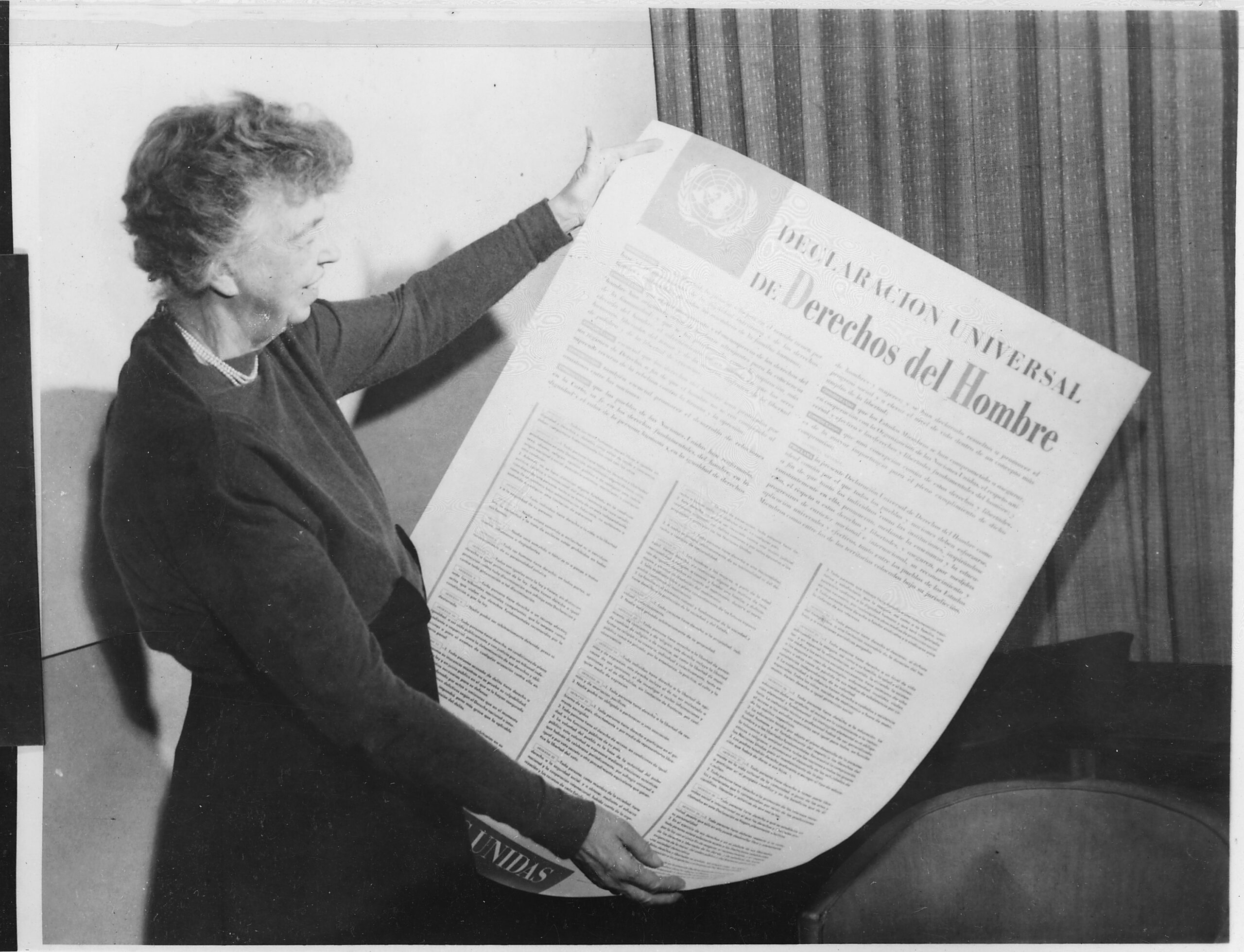

The momentum towards codifying human rights began outside Canada soon after the Second World War. The UN’s founding charter included a mandate to promote human rights. In 1948 the Organization of American States produced the American Declaration of the Rights of Man, and the UN General Assembly approved the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. But it was the UDHR that became a potent symbol. Anticolonial movements, especially in Africa, drew on the language of the UDHR. Twelve new African nations incorporated part or all of the UDHR in their constitutions. The European Convention on Human Rights (1950), inspired in part by the UDHR, created the first regional enforcement mechanism for human rights: the European Court of Human Rights. The first global human rights treaties were also a legacy of the UDHR: the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (1967) and the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Political Rights (1967). Meanwhile, a global human rights movement was taking shape. There was already the International Labour Organization (1919), Fédération internationale des ligue des droits de la personne (1922), Freedom House (1941), and the International League for the Rights of Man (1942). But it was the founding of Amnesty International in 1961 that heralded a new era of transnational human rights activism. In Canada, dozens of human rights and civil liberties groups were founded in the 1960s.