In 1945, Alistair Stewart, recently elected member of the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (CCF), presented before Parliament the first resolution to create a Canadian Bill of Rights. The CCF’s Regina Manifesto, its founding document of 1933, had called for amendments to the Constitution to protect racial and religious minorities, and to offer greater protection for freedom of speech and of association. Only a year before Stewart introduced his motion, the civil liberties subcommittee of the Canadian Bar Association had recommended entrenching certain rights in the Constitution.

Opponents of a bill of rights appealed to the notion of parliamentary supremacy. In the British tradition, Parliament was supreme and could not be overruled by the courts. Unlike Great Britain, Canada had a written constitution that was enforced by the courts, but because it did not contain a bill of rights, the primary role of the courts on constitutional matters was to determine whether a particular issue came under provincial or federal jurisdiction. For instance, when Ottawa challenged a 1937 Alberta law that placed restrictions on banking and the press (Act to Ensure the Publication of Accurate News and Information), the court’s responsibility was simply to determine whether the law fell under provincial or federal jurisdiction, not to state whether it violated free speech or the right to a free press. (It concluded that the law fell within federal jurisdiction and declared it inoperative.) Thus, in defending the actions of his government in suspending habeas corpus and other civil liberties in 1946 (see Gouzenko), Minister of Justice J.L. Ilsley claimed that “those principles resulting from Magna Carta, from the Petition of Rights, the Bill of Settlement and Habeas Corpus Act, are great and glorious privileges; but they are privileges which can be and which unfortunately sometimes have to be interfered with by the actions of Parliament or actions under the authority of Parliament.” [Hansard, 1947] In Ilsley’s view, a bill of rights that was intended to limit parliamentary supremacy threatened to Americanize the Canadian political system. No less than three federal investigations were initiated between 1948 and 1950 to consider the viability of a national bill of rights. In each case, the investigating committees rejected a constitutional amendment.

Over the next few decades, opposition to a bill of rights gradually eroded. Alberta attempted to pass its own example in 1946, but it was struck down by the Supreme Court of Canada. A breakthrough occurred in Saskatchewan in 1947 when the CCF, led by Tommy Douglas, introduced the country’s first bill of rights, but it applied only in Saskatchewan. The Canadian Congress of Labour began advocating for a national bill of rights as early as 1947, and the Trades and Labour Congress followed suit in 1948. Among the few civil liberties associations that were active in Canada, support for a bill of rights was virtually unanimous. At a December 1946 conference in Toronto to discuss common strategies, civil liberties groups from Ottawa, Montreal, and Toronto all expressed their support for a constitutionally entrenched bill of rights.

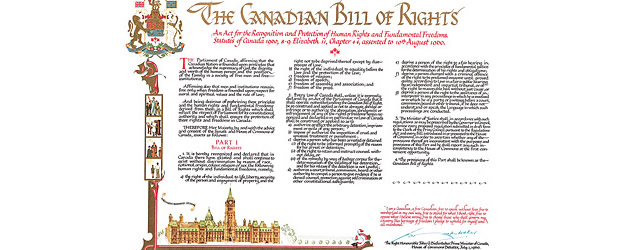

The movement for a bill of rights was an important step in acknowledging the compatibility of constitutional rights with the Canadian political system. By 1960, as John Diefenbaker’s Conservative government prepared to enact its own bill of rights, the notion of parliamentary supremacy was waning. Davie Fulton, Diefenbaker’s minister of justice, was not opposed to a constitutional amendment, and in fact, he favoured a bill of rights that was binding on the provinces. In his presentation to the parliamentary committee that was considering the government’s proposed legislation, Fulton did not invoke parliamentary supremacy to explain his government’s decision to introduce a statute rather than a proposed constitutional amendment. Instead, he discussed the legal and political obstacles to amending the Constitution. Specifically, Fulton was concerned with the lack of an amending formula and the implications of having Britain amend the Constitution on behalf of Canada, which was in the process of distancing itself from the mother country. The 1960 federal Bill of Rights, which purported to empower judges to veto legislation that violated fundamental freedoms such as free speech or due process, was a radical departure from a political tradition in which the courts did not challenge legislation passed by Parliament unless it was beyond the government’s jurisdiction.

However, the 1960 Bill of Rights was a dismal failure. As Frank Scott noted in 1964, “that pretentious piece of legislation has proven as ineffective as many of us predicted.” [Clément 2008] The Bill of Rights suffered a painful reception at the hands of the judiciary. In Robertson and Rosetanni v. The Queen (1963), the Supreme Court of Canada rejected arguments that the Lord’s Day Act (which banned businesses from operating on Sundays) violated freedom of religion under the Bill of Rights. According to Justice Ronald Ritchie, in his decision for the majority, the Bill of Rights enshrined only those rights that had existed immediately before it was passed in 1960. It created no new rights, and since freedom of religion already existed before 1960, there was no basis for making the Lord’s Day Act inoperative. By 1969, the court had yet to use the Bill of Rights to assert an individual’s civil liberties against the state. Even the famous Drybones case of 1970, in which the court ruled section 94(b) of the Indian Act inoperative because it violated the “equality under the law clause” of the Bill of Rights, failed to set an effective precedent (the section of the Indian Act prohibited Aboriginals from being intoxicated off reserves). In 1974, the court reversed itself in Attorney General of Canada v. Lavell. The case, appealed to the court by Jeannette Lavell and Yvonne Bédard, dealt with the section of the Indian Act that deprived women of their Indian status if they married a non-Indian. The court refused to accept that the Indian Act violated equality under the law. Once again writing for the majority, Ritchie suggested that to accept Lavell’s claim would essentially invalidate Ottawa’s ability to designate special treatment for Native people and thus render it impotent in carrying out its responsibilities under the Constitution. In effect, the judgment meant that Aboriginal women could be discriminated against as long as the discrimination applied equally to all of them.

Subsequent attempts to use the equality under the law clause to render legislation inoperative were equally fruitless. Of the thirty-five claims brought under the Bill of Rights between 1960 and 1982, only five were successful and just one resulted in striking down legislation. However, this catalogue of failure ultimately gave rise to success. The inability of the Bill of Rights to provide concrete protection for human rights led activists and policy-makers alike to demand a constitutional amendment in 1982. The resulting Charter of Rights and Freedoms would transform the courts into a far more active agent in combating human rights violations.

Further Reading

- Clément, Dominique. Canada’s Rights Revolution: Social Movements and Social Change, 1937-82. Vancouver: UBC Press, 2008.

- MacLennan, Christopher. Toward the Charter: Canadians and the Demand for a National Bill of Rights, 1929-1960. Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2003.

- Tarnopolsky, Walter. The Canadian Bill of Rights. Toronto: Carswell, 1966.