Human Rights Activism

| Copyright Dominique Clément / Clément Consulting

A parallel human rights movement was emerging alongside the rights associations that campaigned against state abuse of civil liberties. This movement was primarily concerned with discrimination in the public and private realm. Discrimination was a fact of life in Canada by the mid-twentieth century, and immigration policies were explicitly racist. Thousands of Canadian citizens of Japanese descent were deported to Japan in the aftermath of the Second World War. During the war, Canada was among the world’s least hospitable destinations for Jewish refugees, barely five thousand of whom were allowed to enter the country. Recruiting centres rejected visible minorities who sought to enlist. Barbers refused to serve blacks; taverns posted signs reading “No Jews or Dogs Allowed”; golf courses banned racial and religious minorities; hotels excluded Aboriginal people; blacks were refused service in bars and segregated in theatres; and landlords refused to rent apartments to visible or ethnic minorities. Aboriginal people were not permitted to hire legal counsel to sue the government, a prohibition that was not eliminated until 1951. The federal ban on Aboriginal political organizing and land claims, instituted in 1927, was also lifted in that year. Minorities were regularly denied licences to operate businesses. Ontario and Saskatchewan prohibited white women from working for Chinese employers. Schools in Nova Scotia and southern Ontario segregated blacks and whites. Most visible minorities could not vote, and in 1945 the BC legislature rejected a Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (CCF) motion to enfranchise Asian Canadians (meanwhile, the federal government disenfranchised Japanese Canadians). Jehovah’s Witnesses, whose pamphlets referred to the Catholic Church as the “whore of Babylon,” were routinely persecuted and jailed. An economic campaign in Quebec during the war, achat chez nous, encouraged French Canadians to boycott Jewish businesses. Such was the pervasiveness of anti-Semitism that even Jewish businesses sometimes refused to hire Jews.

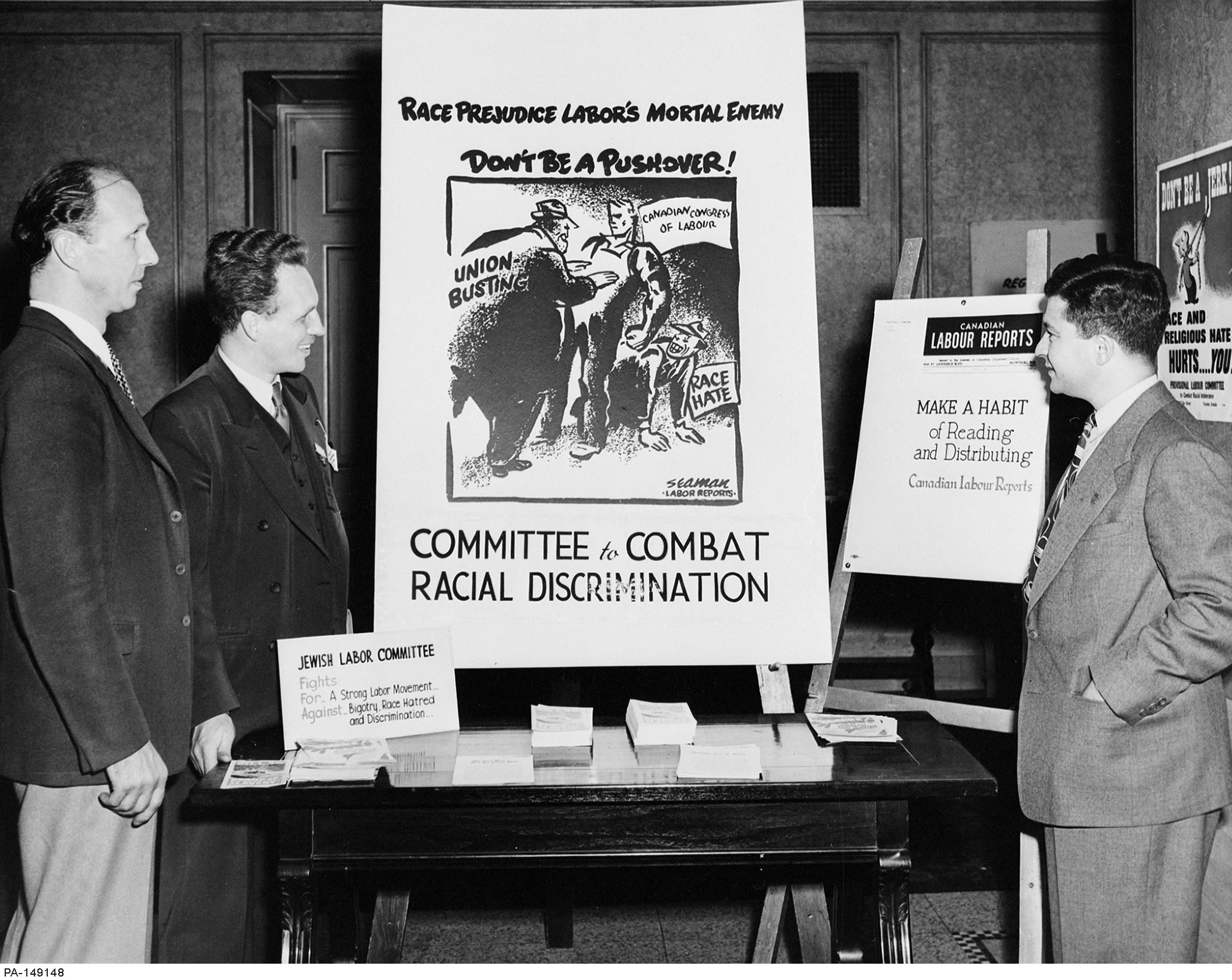

The campaign for anti-discrimination legislation often coalesced around an organization called the Jewish Labour Committee (JLC). The JLC and the Joint Public Relations Committee (an alliance of the Canadian Jewish Congress and B’nai Brith) were established in 1936 and 1938 respectively. Working together, they created Joint Labour Committees to Combat Racial Discrimination in Toronto, Windsor, Montreal, Vancouver, and Winnipeg, which were “jointly” funded by the Canadian Labour Congress and the Trades and Labour Congress. A central figure in this movement was Montreal-based Kalmen Kaplansky. A Polish-born war veteran who was fluent in Yiddish and English, Kaplansky was appointed national director of the JLC in 1946. He essentially ran the committees. His ties to the International Typographical Workers’ Union and the CCF were invaluable assets for forming alliances among politicians, unions, and religious and minority organizations. The JLC was an extraordinarily influential organization and one of the few social movement associations in Canada with a genuine national reach.

Organized labour – often working alongside minorities who were victims of discrimination – was also at the forefront of campaigns for anti-discrimination legislation. This had not always been the case. For many years, labour leaders had portrayed immigrants and racial/ethnic minorities, most notably the Chinese in British Columbia, as low-wage strike-breakers who threatened to undermine organized labour. At the inaugural meeting of the Canadian Brotherhood of Railway Workers, the most powerful labour union at the time, the membership agreed that only white men would be allowed to join. Changes in the labour force and the need for working-class unity had a profound impact on the labour movement. This was evident in the CCF’s founding program, which called for a bill of rights that would ban discrimination. Racial minorities also took an active role in challenging their own marginalization. In 1946, for instance, a group of Chinese Canadians formed the Committee for the Repeal of the Chinese Immigration Act to lobby for the removal of a ban on Chinese immigration to Canada. The Jewish Labour Committee, though, was especially prominent, and it established several offices across Canada to lobby for anti-discrimination legislation. It campaigned alongside civil liberties groups in Vancouver, Montreal, and Toronto throughout the 1950s.

A breakthrough occurred in Saskatchewan in 1947, when the CCF, led by Tommy Douglas, passed the country’s first bill of rights, the Saskatchewan Bill of Rights (which was applicable only in that province). In Ontario, the Jewish Labour Committee and the Civil Liberties Association of Toronto successfully mobilized dozens of organizations to lobby for legislation that banned discrimination. Their efforts bore some fruit in 1951, when Premier Leslie Frost’s Conservative government passed Canada’s first Fair Employment Practices legislation, followed soon afterward by a Female Employees Fair Remuneration Act and a Fair Accommodation Practices Act. Within five years, similar laws were passed in five other provinces. Another landmark achievement of the early human rights movement was the 1960 enactment of a federal Bill of Rights under the Conservative government of John Diefenbaker. In many ways, these developments were revolutionary. True, the legislation was often poorly designed and impossible to enforce. Still, in the past, the courts had favoured the rights of the discriminator: the right to freedom of speech or association was interpreted to mean the right to refuse service to certain people or to express prejudicial ideas. In contrast, as James Walker explains in “Race,” Rights and the Law, anti-discrimination legislation “represented a fundamental shift, a reversal, of the traditional notion of citizens’ rights to enrol the state as the protector of the right of the victim to freedom from discrimination. It was, in fact, a revolutionary change in the definition of individual freedom.”

Site Resources

Site ResourcesThe readings lists available on this site deal with a range of topics from human rights to biographies and specific events.

-

- Any use of material or referencing content from HistoryOfRights.ca should be acknowledged by the User and cited as follows:

–

- Clément, Dominique. “page title or document title.” Canada’s Human Rights History. www.HistoryOfRights.ca (date accessed).

History

History

© 2024 COPYRIGHT CLÉMENT CONSULTING. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

DEPARTMENT OF SOCIOLOGY, UNIVERSITY OF ALBERTA

© 2024 COPYRIGHT CLÉMENT CONSULTING. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

DEPARTMENT OF SOCIOLOGY, UNIVERSITY OF ALBERTA